Now that is crazy.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Great Big Stories : People Eating Together

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

ideas : People : stories.

the Human Being stuff

Now that is crazy.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Great Big Stories : People Eating Together

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

There isn't much to add to this because it's pretty spot-on. My only even minor critique would be that if our only goal is to win someone to our side, than all the gimmicks we employ to trick someone into thinking we are on their side, that we are listening, and that we care what they are saying, that we are just as selfish someone who is simply trying to win an argument. We're just not as brash about it.

However, I don't think that is the point of this video, especially when Fred Rogers is used as the example, but I still think it needs to be said - for me at least.

A true and meaningful discussion points towards a higher and greater truth; it means both are willing to refine and tweak their own thinking, for the sake of a greater cause.

But I think the point in all of the above is this: in order to be heard, we have to be relational - fully and completely. Dogmatism beats the elephant; sincere persuasion gives it goosebumps.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Diversity Makes Us Smarter : Elements of a good Discussion : Mr. Rogers' Sweaters

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

Film without soundtracks are boring, and the art of creating a story in sound, a story that not only enhances the movie but takes over the mind of a listener, is an art that stands alone.

Ramin Djawadi, a talented musician most known for composing the music for Game of Thronesparticularly the iconic theme, shared his thoughts around how he scores a soundtrack for such a varied series. Djawadi, who started playing music at a very young age, explained how he was attune to the need for musical themes, but wanted to introduce them in such a way as to not overwhelm the audience (via).

The biggest challenge was just finding the right tone for the show, that when you hear the score, that you know this is Game of Thrones. From the beginning, we knew we wanted themes, but we also knew that we couldn’t have too many themes right away, because there’s obviously a lot of characters. There’s a lot of different houses, there’s a lot of plots. And if you convolute it too soon, I think it actually would have been confusing for the audience.

One of the greatest, Hans Zimmer,

Some of my favorite soundtracks include, but are not limited to:

The Dark Knight, Rudy, Transformers, Rush, About Time, The King's Speech, Band of Brothers, How to Train Your Dragon (Forbidden Friendship might be one of the best songs, ever), Legends of the Fall, Dances with Wolves, Memoirs of a Geisha, Saving Privet Ryan, Last of the Mohicans, and Finding Neverland - just to name a few.

There is also some great soundtrack stations on youtube that are inspiring, calming, epic, and simply beautiful.

If you have some favorites, list them below! I'd love to add them to the collection.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Movies Without Soundtracks : Music

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

Filmmaker Neill Blomkamp (District 9, Chappie) is planning on making a series of experimental short films as proofs-of-concept for possible feature film development. His first short has just been released through Oats Studios; it’s called Rakka, stars Sigourney Weaver, and is kind of a cross between District 9 and Edge of Tomorrow (via).

These futuristic/alien takeover sort of movies, for me, are always a hit or miss. What I do like about them though, and this one seems to be of a similar cut, is that they bring humanity to the edge of extinction and then ask, "What does it mean to be human?"

If we survive, but at the sacrifice of morals, of humanity, is life worth living?

The Walking Dead asks the same question. So does Ivan Denisovich. Because conflict - true and meaningful conflict - reveals truth. Truth about ourselves, and truth about our world.

I'm intrigued by Amir and what part he will play. How will his fractured humanity impact the world? Will it win? Or will it succumb?

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Short Films : Humanity

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

"In 1846, large numbers of women and babies were dying during childbirth in Vienna. The cause of death was puerperal fever, a disease that swells then kills its victims. Vienna's General hospital had two maternity clinics. Mothers and newborns were dying in only one of them. Pregnant women waited outside the hospital, begging not to be taken to the deadly clinic, often giving birth in the streets if they were refused. More women and babies survived labor in the streets than in the {deadly} clinic. All the deaths came at the hands of doctors. In the other clinic, midwives delivered the babies" (pg 72, bolding mine).

This, an excerpt from the book How to Fly a Horse, by Kevin Ashton. Earlier in the book, Ashton writes, "Thinking is finding a way to achieve a goal that cannot be attained by an obvious action," and which is now underlined, along with a few other quotes on several other pages. Ashton is writing this book in hopes of squashing the belief that creation, invention, and discovery are only set aside for a select few, and that that happen in a moment of intense inspiration. "Creation," he writes, "is a destination, the consequences of acts that appear inconsequential by themselves but that, when accumulated, change the world. Creating is an ordinary act, creation its extraordinary outcome" (pg 23), and it can be done by anyone, not just the elite or the ultra brilliant because, "Everyone is born creative; everyone is given a box of crayons in kindergarten. Being suddenly hit year later with the 'creative bug' is just a wee voice telling you, 'I'd like my crayons back, please'" (pg 18).

Is this why doctors - not midwives, were responsible for the deaths of hundreds of mothers and newborns in the 1800's Vienna? Because they considered themselves the elite and professional and no longer in need of curiosity? Innovation? And discovery?

Maybe.

Ashton continues. "Vienna General was a teaching hospital where doctors learned their trade by cutting up cadavers. They often delivered babies after dissecting corpses. One of the doctors, a Hungarian named Ignaz Semmelweis, started to wonder if the puerperal fever was somehow being carried from the corpses to the women in labor. Most of his peers thought the question preposterous. Carl Edvard Marius Levy, a Danish obstetrician, for instance, wrote that Semmelweis's 'beliefs are too unclear, his observation too volatile, his experiences too uncertain, for the deduction of scientific results.' Levy was offended by the lack of theory behind Semmelweis's work. Semmelweis speculated that some kind of organic matter was being transferred from the morgue to the mothers, but he did not know what it was. Levi said this made the whole idea unsatisfactory from a "scientific point of view."

"But, from a clinical point of view, Semmelweis had convincing data to support his hypothesis. At a time when doctors did not scrub in or out of the operating room, and were so proud of the blood on their gowns that they let it build up throughout their careers, Semmelweis persuaded the doctors of Vienna to wash their hands before delivering babies, and the results were immediate. In April 1847, 57 women died giving birth in Vienna General's deadly First Clinic - 18 percent of all patients. In the middle of May, Summelweis introduced hand washing. In June, 6 women died, a death rate of 2 percent, the same as the untroubled Second Clinic. The death rate stayed low, and in some months fell to zero. In the following two years, Semmelweis saved the lives of around 500 women, and an unknown number of children."

"This was not enough to overcome the skepticism. Charles Delucena Meigs, and American obstetrician, typified the outrage. He told his students that a doctor's hands could not possibly carry disease because doctors are gentlemen and 'gentlemen's hands are clean'" (pg 73).

Which also means, ironically, that the most deadly clinic was probably made up of all men, while the second clinic, the safer and more reliable one, was filled with older women - midwives - who relied on the practical experience they received in delivering many children. Women who weren't so concerned about the blood on their gowns as they were about the babies being born and the mothers who carried them.

"Semmelweis did not know why hand-washing before delivery saved lives- he only knew that it did. And if you do not know why something saves lives, why do it? For Levy, Meigs, and Semmelweis's other 'gentlemen' contemporaries, preventing the deaths of thousands of women and their babies was not reason enough" (pg 73).

If this is a gentleman, I hope to never be confused as one again. Sheesh.

"As the medical community rejected Semmelweis's ideas, his moral and behavior declined. He had been a rising star at the hospital until he proposed hand-washing. After a few years, he lost his job and started showing signs of mental illness. He was lured to a lunatic asylum, put into a straightjacket, and beaten. He died two weeks later. Few attended his funeral. Without Semmelweis's supervision, the doctors at Vienna General Hospital stopped washing their hands. The death rate for women and babies at the maternity clinic rose by 600 percent."

What a tragic ending and lack of recognition to a man who saved thousands of lives.

Why did so few attend his funeral? Why did so few listen to his advice? And why was the practice of washing hands so difficult to embrace?

"Because," Ashton write, "When you bring something truly new to the world, brace. Having an impact is not usually a pleasant experience. Sometimes the hardest part of creating is not having an idea but saving an idea, ideally while also saving yourself."

This tragic truth seems to affirm itself throughout history, and the root cause of it all seems to be pride.

Ashton concludes this section with this. "William Syrotuck analyzed 229 cases of people who became lost, 25 of who died. He found that when we are lost, most of us act the same way. First, we deny that we are going in the wrong direction. Then, as the realization that we are in trouble seeps in, we press on, hoping chance will lead us. We are less likely to do the thing that is most likely to save us: turn around. We know our path is wrong, yet we rush along it, compelled to save face, to resolve the ambiguity, to achieve the goal. Pride propels us. Shame stops us from saving ourselves" (pg 90).

I can imagine that, for those doctors, to start washing hands - and to commit to it - would be to admit fault, that those deaths were in fact their fault. And I can also imagine that that truth would be drastically hard to swallow. So they pressed on, hoping chance would free them from guilt.

To turn around - to repent - means to admit fault and to acknowledge that, somewhere along the way, we made the wrong turn. Every wanna-be hero is brought to this point. The hero hits the breaks and turns the wheel; the tragic hero continues on, propelled by pride, as hundreds of women and children needlessly pass away.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : The DR Who Championed Hand-washing : Humilitas : Hero's Journey

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

I've always struggled with the concept of success because it seems to carry the idea of money and fame. I've argued, on more than one occasion, that being successful doesn't necessarily mean money, but rather, the accomplishment of something. Yet, in a recent conversation with my little sister I found myself saying, and believing, that I haven't found success in a few of my endeavors because no one is willing to pay for them, because I'm doing them on my own time, for free. Success, apparently, is marked by the dollar sign, because, whether I like it or not, we put our money where our mouth is.

Like many of my friends I've talked with over the years, the idea of obtaining this kind of success, the kind that reaches beyond personal gratification and lives in the land of compensation, seems to dependent upon skills and talents, time and resources, and the many other factors that we don't seem to have. Which is why we haven't found success, and perhaps never will.

Recently, though, I've been encouraged by a different notion, that talents and time and resources can aid in the acquisition of success, but they are not the greatest determiner. More than any of these, passion and perseverance (earnestness even) and the relentless pursuit of one's commitments is what determines success.

Angela Duckworth calls this "grit."

Angela Duckworth is smarter than me, and for sure much more successful, but I'm not quit sure I believe her conclusion of "we don't know," because I think we do know, and I think it has to deal with the very idea she is presenting - grit. We teach our kids grit.

As a child, I remember - often - working with my dad on tasks and projects I didn't really care to be a part of. Things like, chopping wood all Saturday, shoveling the the long driveway, raking leaves, and various other tasks. When I complained or argued, my father made me do them anyway. Before playing with friends or watching t.v.. I remember being so frustrated and angry because all I wanted to do was be with my friends, not working. I also remember, even though I would never admit it to him and only barely admitted to myself, that when the job was completed, I would look at what I had done and feel a sense of accomplishment and be proud of what I had done.

Looking back, it was during these times that the seeds to success were being planted.

As parents, as educators, we can teach our kids grit by providing opportunities for them to struggle, sweat, and endure through difficult tasks. Tasks like overcoming difficult hikes, persevering through piano or guitar lessons, and even pulling nails from old pallets. They might complain, but if the task has purpose, if they can see that there is a reason for all their hard work, when it is over, when the bench and drawer are built, whether they admit it or not, there will be a sense of accomplishment, because they gritted through.

Duckworth ends her talk without much conclusion, but rather, a charge - to be "gritty about getting our kids grittier." I think we can do this by being purposeful about getting our kids engaged in tasks that demand hardship and difficulty and, most importantly, longevity, but that are also full of purpose.

For more talks and ideas of Success, you can listen to this TED Radio Hour appropriately entitled, Success. It's a great listen and worth the 50 minutes.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : TED Talks : Growth Mindset : Creativity in Education

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

I watched this on the flight back to the US and frigging LOVED it. The slow pace, the dichotomous characters, and the simplistic message of life and love. The beauty of small town living.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Movies : Some (possible) great new movies

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

By, Wendell Berry

Make a place to sit down.

Sit down. Be quiet.

You must depend upon

affection, reading, knowledge,

skill - more of each

than you have - inspiration,

work, growing older, patience,

for patience joins time

to eternity. Any readers

who like your work,

doubt their judgement.

Breathe with unconditional breath

the unconditioned air.

Shun electric wire.

Communicate slowly. Live

a three-dimensioned life;

stay away from screens.

Stay away from anything

that obscures the place it is in.

There are no unsacred places;

there are only sacred places

and desecrated places.

Accept what comes from silence.

Make the best you can of it.

Of the little words that come

out of the silence, like prayers

prayed back to the one who prays,

make a poem that does not disturb

the silence from which it came.

From, Given Poems

WENDELL BERRY, writer, poet, teacher, farmer, and outspoken citizen of an endangered world, gives us a compelling vision of the good and true life. Passionate, eloquent, and painfully articulate, in more than fifty works – novels, short stories, poems and essays -- he celebrates a life lived in close communion with neighbors and the earth while addressing many of our most urgent cultural problems. A fierce and caring critic of American culture and a long-time trusted guide for those seeking a better, healthier, saner world, he has farmed a hillside in his native Henry County, Kentucky, together with his wife, for more than forty years.

Over the years, Berry has received the highest honors including the National Medal of Arts and Humanities, a National Institute of Arts and Letters award for writing, and theAmerican Academy of Arts and Letters Jean Stein Award. Much has been said and written about his work (via).

A documentary on him, his work, and his farm life is coming out this fall. It's entitled "Look & See: A Portrait of Wendell Berry." You can watch the trailer here.

"As I see," Wendell Berry writes, "the farmer standing in his field, is not isolated as simply a component of a production machine. He stands where lots of lines cross – cultural lines. The traditional farmer, that is the farmer who was first independent, who first fed himself off his farm and then fed other people, who farmed with his family and who passed the land on down to people who knew it and had the best reasons to take care of it... that farmer stood at the convergence of traditional values... our values" (via).

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Poetry : Wendell Berry Literature

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

"To be precise, 54 years, 8 months, 6 days, 5 hours, 32 minutes and 20.3 seconds was how long it took Shiso Kanakuri to finish the race — not that the time, which was only ever recorded as a joke, matters. It’s Kanakuri himself who is important, because when he set off on that infamous run, {a little over} 100 years ago in Stockholm, he was one of just two athletes representing Japan at its very first Olympic Games"

"Sport had not been a particularly popular pastime in early 20th-century Japan. Fledgling clubs catering to various physical activities had popped up at schools and universities, but, as the historian Kazuo Sayama has written, 'there had been martial arts in Japan, but they were very different to the French idea of sport. (In the early 1900s) few Japanese had awoken to sport’s real meaning.'"

"The French reference is crucial, because it was that country’s notion of sport that informed the 1896 revival of the Olympic Games in the modern era. Part of that idea, as promoted by the International Olympic Committee’s inaugural chairman, a Frenchman named Pierre de Coubertin, was that sport was a progenitor of peace, and hence the participation of all the races was to be encouraged."

"After the London Olympics of 1908, Coubertin decided it was time for Asians to join the fray, and so he arranged for a Japanese representative to join the IOC. The man who got the nod was the well-respected judo wrestler Jigoro Kano (later known as the “father of modern judo”), who shortly set about holding athletics trials for the next Olympics, which would be held in Stockholm in 1912."

"The trials for the marathon were held on Nov. 19, 1911, and one of the competitors was a 20-year-old student from the Tokyo Higher Normal School named Shiso Kanakuri (his name is sometimes rendered Shizo Kanaguri). Originally from an area of Kumamoto Prefecture in Kyushu now known as Tamana, his initial approach to running, as reported by Sayama in a biography published last year, was indicative of the lack of experience among his countrymen."

"'There was a belief at the time that perspiration made runners tired,' Sayama explains, before noting that 'Kanakuri’s initial approach was to abstain from any drink at all, at one time making himself sick.'"

"Fortunately, by the time of the trials, Kanakuri had come to appreciate the importance of proper hydration, and he flew around a roughly 25-mile (40.2 km) course in 2 hrs. 32 min. 30 sec., well ahead of his rivals."

"Kanakuri was thus in the team, and he was soon joined by a short-distance specialist named Yahiko Mishima from Tokyo Imperial University (forerunner of the University of Tokyo). With the addition of Kano, as Chef de Mission, and also physical-education specialist Hyozo Omori, as team manager, the party that would travel to Stockholm was complete."

"On May 16, 1912, The Japan Times noted their departure with an article that both lowered and raised expectations: 'As this is the first time Japanese runners (or any Japanese athletes) have taken part in these world-contests, it is impossible to say what they will achieve. But both are full of grit and nerve, and may be counted upon for doing credit to themselves and to Japan.'"

"But lack of experience was not the only thing working against the Japanese runners. There was also the fact of the 10 days to be spent on the Trans-Siberian Railway, when opportunities to train would be at a minimum. "'Kanakuri took to running around each station that they stopped at,' Sayama writes."

"At Stockholm, things didn’t improve. Omori soon fell ill, and so Kanakuri, the youngest in the group, ended up spending more time looking after him than training. (Incidentally, Omori is now known as 'the father of Japanese basketball,' because, in 1908, he brought back that sport from the United States, where he had studied.)"

"The day of the Stockholm marathon, July 14, 1912, was a scorcher. A photograph of the 68 runners at the start line shows them all wearing hats or towels around their heads — a somewhat quaint attempt to deal with the 32-degree heat."

"According to Sayama, Kanakuri later recalled how the other runners had been surprised at his footwear: tabi, the two-toed canvas shoes still worn by some workers on construction sites. Although Kanakuri’s were fortified with extra canvas on their soles, they wouldn’t have afforded much protection."

"Still, they were probably better than spikes, which is what the Japanese media somehow decided Kanakuri had worn as they later tried to explain the disaster that was about to unfold."

"Somewhere around the 27-km mark, Kanakuri collapsed, probably from hyperthermia (in simple terms, extreme overheating). It is believed he briefly lost consciousness before being taken to the house of local residents who assisted him."

"Kanakuri’s withdrawal from the race was hardly unusual. After all, only half the 68 starters ended up finishing the race. What was unusual was that he didn’t notify the event officials. They duly listed him as 'missing.'"

"The Japanese runner was likely too dispirited by his failure to worry about filling in the proper paperwork. Sayama reports that in his diary Kanakuri lamented bringing 'shame' to his countrymen, but at the same time he struck an optimistic note: 'This failure will beget success,' he vowed."

"Although The Japan Times was among the media that blamed Kanakuri’s failure on an erroneous assumption about his footwear, it was nevertheless kind to both him and Mishima (who failed to get through to the finals of his 100-, 200- or 400-meter races)."

"'It will be unfair to deal harshly with these young athletes for their faults,' an unidentified scribe wrote on July 21, 1912. Instead, that same writer dealt harshly with a system that had sent unprepared athletes onto the world stage in the first place."

"Noting that the ultimate winner of the marathon, Kennedy Kane McArthur of South Africa, had spent 2½ years preparing for the race, the writer demands that no more athletes be sent abroad "'except with the most serious determination and all possible preparedness.'"

"Kanakuri seems to have agreed. On his return to Japan, he immediately began preparing for the Berlin Olympics, which were due to be held in 1916. However, World War I put paid to that athletics festival, and another four years later, at age 28, Kanakuri competed in the marathon at the Antwerp Olympics in Belgium — finishing a creditable 16th. In 1924, he competed in Paris, too, but had to retire halfway through the race."

"In the meantime, Kanakuri achieved what is now his greatest legacy: the Hakone Ekiden, the 218-km team relay contested by universities from around the nation each New Year’s. Kanakuri played a key role in establishing that race officially known as the Tokyo-Hakone Round-Trip College Ekiden Race, which ever since its inauguration in 1920 has helped popularize long-distance running among Japan’s youth."

"Then in 1967, when Kanakuri was 75 years old and no doubt reflecting on a long and illustrious career, he received an odd invitation. The Swedish National Olympic Committee wanted him to return to Stockholm to participate in the 55th anniversary celebrations of the 1912 Olympics."

"Kanakuri should have realized that 55 was an odd anniversary to celebrate. Upon his arrival in the Scandinavian country he was informed that he had become known there as 'the missing marathoner' — the man who had vanished without a trace all the way back in 1912."

"And thus, for the benefit of the local media and the Swedish NOC, which was then trying to raise funds to send athletes to the following year’s Olympic Games in Mexico, Kanakuri was asked to 'finish' the race."

"Judging by press reports of the proceedings, the elderly gent was only too happy to oblige, running jovially around the last corner before charging through a special ribbon."

"His time was promptly read out — 54 years, 8 months, 6 days, 5 hours, 32 minutes and 20.3 seconds — and, according to Sayama, the elderly racer then responded: 'It was a long trip. Along the way, I got married, had six children and 10 grandchildren.'"

"The apparently modest Kanakuri could have boasted of having another 'child,' too. After all, by then he was known in his home country as 'the father of Japanese marathon'" (via).

I just love this story.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Real People : Humanity

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

I'm not a big fan of the word "success" because its connotations tend to deal with money and fame, which seem to be incomplete determiners of success. So, instead of "successful," creative - or perhaps even content - is a better fit. The descriptors still falling neatly into place.

: Edit - 6/22/17 :

A good friend of mine, Eric Trauger, mentioned two additional words: progressive (as in progress - the moving advance or development toward a better, more complete, or more modern condition) and earnest.

I like these additions because they broaden the range a bit, especially earnest. Earnest, serious in intention, purpose, or effort - sincerely zealous - or, showing depth and sincerity of feeling, to me, carries more intentionality than the others. It switches the order.

If someone reads books, forgives, collaborates, etc, than they are creative, content, or progressive; they are are the effects of, not the cause. Living an earnest life, however, seems a more conscious decision - it is the cause, not the effect.

All this, though, and perhaps most importantly, points to the idea that a "successful" life - a life marked by creativity, progress, and earnest living - is fully intentional, not accidental. It is a daily decision, a daily battle, to live with purpose and conviction, and to live outside of redundancy and monotony.

To watch TV, or read. To encourage rather than criticize. To be thankful, not entitled. Strangely, it seems, life can be defined by these simple things. Which is encouraging, I think, and a bit terrifying.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Inspiration : Creativity

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

Below is a short excerpt from a film entitled, "Human" by Yann Arthus-Bertrand.

"I am one man among seven billion others" Bertand writes. "For the past 40 years, I have been photographing our planet and its human diversity, and I have the feeling that humanity is not making any progress. We can’t always manage to live together.

Why is that?

I didn’t look for an answer in statistics or analysis, but in man himself."

Yann Arthus-Bertrand was born in 1946, and has always nurtured a passion for animals and the natural world. At a very early age, he began to use a camera to record his observations and accompany his writings.

On the occasion of the first Earth Summit in Rio in 1992, Yann decided to embark upon a major photographic project about the state of the world and its inhabitants: Earth From Above. This book enjoyed international success, selling more than three million copies. His open-air photographic exhibition was shown in around 100 countries and seen by some 200 million people.

Yann continued his commitment to the environmental cause with the creation of the GoodPlanet Foundation. Since 2005, this non-profit organization has been investing in educating people about the environment and the fight against climate change.

This commitment saw him appointed United Nations Environment Program Goodwill Ambassador in 2009. That same year, he made his first feature-length film, HOME, about the state of the planet. This movie was seen by almost 600 million spectators around the world (via).

You can watch the full-length movie here.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Humanity : On Living

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

"Climbing the Wall was very scary in the beginning," Judah writes in his journal, "but as we got to the fourth tower, it got a lot more fun and I got more brave."

A little over a year ago, I mentioned to Josey (my wife) that I would like to take a small trip with Judah to the Great Wall. She thought it was a good idea too, but the conversation somewhat ended as soon as it started, because there wasn't time in our schedule - we were soon planning to have our fourth child and move back to the States. Near the halfway point of our last hundred days however, she brought it up again and suggested maybe we look into it - as a sort of last goodbye to our five years in China.

In the coming months, the idea began to gain momentum and my journal slowly accumulated ideas and plans for the trip. Some of which would come to fruition, others would not, and that was fine because what I unexpectedly gained was the chance to watch my son, over the course of a couple hours, overcome his fears and learn foundational life-lessons. All because we made time to hike the Great Wall of China.

The Great Wall of China is long, 21,196 km (13,171 mi) long, and it holds some of the most splendid and awe-inspiring images Google can offer. But we didn't go to those places. Instead, we went further north, where the Wall has not been refurbished, where portions appear more like raised dirt paths than an ancient impenetrable barrier, and where we could stay the night without being bothered.

Isolated, we walked on the original, untainted yet weathered, Great Wall of China.

From the beginning, the path was tough. Often, the stairs were higher than Judah's knees, a few sections required straight up climbing, and at all times, the terrain was rough and uncertain. Steep edges plunged down on either side. For a ten-year old boy carrying a fifteen-pound pack (there were no lakes or streams around, so we had to carry up all our water), it was a bit unnerving. "It's dangerous," he kept saying, hunched over, clinging to the wall with both hands, "We could fall."

At first, I was patient and tried to sooth his fears. Then, as the whining continued and the sun grew more and more hot, I wasn't. "Stop being afraid!" I barked, but it didn't help. Unsurprisingly, it made things worse. Tears came to his eyes. "Just make it to the next tower," I said, "Then we can take a break."

Inside the tower, the temperature dropped about ten degrees and a swift breeze rushed through the windows and doors. We sat, pulled out our lunches and had a talk about fear, about how it's okay to be afraid because it can act as a guide - it can protect us. But also, how it should never control us. "You need to respect the Wall, son, but not fear it. When we climb, we need to be careful and go slow, but we don't need to give in to our fear. We overcome it."

He nodded and said, "okay," but I didn't really know what that meant or if what I'd said mattered. I wasn't sure if he heard me or not. So we finished our lunch and continued, him in the lead and me encouraging from behind, and I watched my son transform. He started attacking the Wall, embracing the harder sections and walking with a confidence and surety he hadn't shown before. The whimpering stopped, his back straightened, and our speed steadily increased. Suddenly, we were hiking the Great Wall of China.

This lesson, this time and transformation of my son, was not listed in my journal prior to the trip, but it presented itself because of the trip, and because I was fortunate enough to be there and to, literally, walk through it with him. On the Great Wall of China! (As often as I write it here, I said it there. Every time we stopped for a break, every tower we summited, and just about every ten minutes or so, I'd say, "Judah, we're on the GREAT WALL OF CHINA!")

Around five-thirty, we reached the last of the towers (there were more, of course, but this one was in the best condition). We set up camp. We rested.

"We put our bags down," Judah writes, "and went up the mountain a little bit more and found a destroyed tower. A whole side of it fell into the inside and me and my dad sat on the edge and looked at the mountains. Then we found some firewood and we started back down and I slipped but I was far from the edge but then gave my firewood to Dad because we were right at the edge."

"Me and my dad." I love that, because that is exactly what this trip was, just us. No cellphones, no computers, and no games. Just us.

And a hammok.

And the sunset.

When the sun went down, we crawled into the tent and read by lamplight. Birds picked at our leftover dinner, the wind shook the flaps of our tent, and Judah asked if I'd rather stay in China or move to America. "I don't know," I answered, "I love them both. What about you?"

"Same." He said. Then we talked about moving from China and leaving family and friends and school and all the things we love about China. This conversation was in my journal of things to do, but coming up this way, in the still of the night, seemed much more appropriate, more natural. And even though it didn't last that long, for Judah, it was enough. Which was enough for me.

That night, we both slept better than expected. I even set my alarm, just in case, and was surprised that I actually needed it. I rolled out of bed around 4:30 but didn't have the heart to wake Judah. The little guy was tuckered.

Right outside the tower, on the edge of the wall, was a small ledge of crumbled stones, and it was just large enough for me to read, drink some coffee, and watch the sun rise in the far, hazy distance.

Judah slept for almost another three hours, allowing me plenty of time to think and consider the last true days of China.

In recent days, the packing and cleaning and scrambling to put the major pieces in play for this trip has stolen any chance of considering all that we're moving toward, and all that we're leaving behind. But, while sitting in the quiet and watching the sun rise, a question finally surfaced, "How can our leaving bless others?" I've been so consumed with what we'll be missing, what we'll be leaving, and how we will be struggling with the transition that I've thought very little of how our leaving could bless others.

It suddenly occurred to me that I've been rather selfish in my final days. That I've been thinking of me and my family, not others. Not how I could bless them and love them, but how they might help me, how they could bless me. Many people did, graciously, but what did I do for them?

Not much.

Before leaving for Beijing, I grabbed a few cards and stuffed them in my backpack, not sure what I might use them for but pretty confident I would need them for something. I snatched them from my bag and pulled the permanent marker from Judah's. Then, I sat and wrote a note. I knew how our leaving could possibly bless someone - even if it was too little too late.

It was time to wake up Judah.

"What are you doing?" he asked after everything was packed. "I'm leaving these here," I said.

"Why?"

"Because it might bless someone."

He was warming his hands by the fire, but then stopped and walked over, "But don't we need them?"

"Need them? No. We could still use them for sure, but don't you think it would be pretty cool to hike all this way and find these nice things?"

"Yeah."

"Well, that's why we're gonna do it. To leave a blessing for someone."

A small smile crept in, "We should leave a note with your email address."

I smiled too, "Already done."

"I have learned two lessons," Judah writes at the end of his journal, "but my dad says I learned three. He says I learned that it's okay to be afraid but fear cannot overcome you, and that dads know everything. I also learned that video games won't teach you anything but physical work can teach you to endure even when you're tired."

Like any other kid, Judah loves playing video games. He's playing one now, as I write, and it is a constant discussion of when and for how long he is allowed to play. Near the end of our journey, at the place where Judah was initially afraid and wanted to stop for the night, I asked him, "Aren't you glad we didn't stop when you wanted? That we kept going to the top."

He laughed a bit, "Yeah. We wouldn't have made it very far."

"Nope," I said.

"I don't know why I was so scared, it really isn't that big of a deal," and we both walked, with ease, over the section that challenged his heart so deeply the day before. Something a video game could never have taught him.

To paraphrase and steal from Thoreau, we went to the Wall because I wished to live deliberately, to suck out all the marrow of our last days in China, and to see if we could not learn what it had to teach. At the end, all my thoughts and emotions are reduce it to its lowest terms...

A night on the Great Wall of China, with my first-born son, to cap off five years living in this beautiful country. I can think of no better way to say goodbye.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Fatherhood : On Parenting

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

Photographer Benny Lam has documented the suffocating living conditions in Hong Kong’s subdivided flats, recording the lives of these hidden communities.

Benny Lam : Wednesday 7 June 2017 07.15 BST

‘I’m still alive and yet I am already surrounded by four coffin planks!’ … Hong Kong’s cage home tenants. All photographs : Benny Lam

Cage homes are minuscule rooms lived in by the poorest people in the city. Over the last 10 years, the number of cage homes made of wire mesh has decreased, but they’ve been replaced by beds sealed with wooden planks

These small, wooden boxes of 15 sq ft, are known as ‘coffin cubicles’

A 400 sq ft flat can be subdivided to accommodate nearly 20 double-decker sealed bed spaces

The tenants are different ages and sexes – all unable to afford a small cubicle, which would allow more room to stand up

A kitchen-toilet complex in a cage home

The photographs highlight the reality of Hong Kong’s housing crisis, where tens of thousands of people live in these cramped conditions because they can’t afford anything else

Many cage home residents awake to the cruel reality that all the shimmer and prosperity of Hong Kong is out of reach

An estimated 100,000 people in Hong Kong live in inadequate housing, according to the Society for Community Organisation (SoCO)

These photographs were taken for SoCO, an NGO fighting for policy changes and decent living standards in the city

Benny Lam’s series Trapped was shortlisted for the Prix Pictet 2017

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Photography : 100x100 Living in Hong Kong

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

OK Computer is 20 years old. To mark the occasion, Radiohead is reissuing the album with three previously unreleased songs from that era (as well as eight B-sides). The album is now available for pre-order and will be released on June 23, but one of the unreleased songs, I Promise, is out now on Spotify, YouTube (see above) and elsewhere (via).

[Verse 1]

I won't run away no more, I promise

Even when I get bored, I promise

Even when you lock me out, I promise

I say my prayers every night, I promise

[Verse 2]

I don't wish that I'm spread, I promise

The tantrums and the chilling chats, I promise

[Refrain]

Even when the ship is wrecked, I promise

Tie me to the rotten deck, I promise

[Verse 3]

I won't run away no more, I promise

Even when I get bored, I promise

[Refrain]

Even when the ship is wrecked, I promise

Tie me to the rotten deck, I promise

[Outro]

I won't run away no more, I promise

At first, I was drawn to this video - even before I knew the lyrics - because the sense of loneliness, isolation, and lost in deep thought was palpable. I was struck too, by the thought, "None of them are on their devices. No one is texting, watching a movie, or listening to music. Everyone is there, fully, and fully alone."

Then came the severed head, and I it lost me.

"In 'I Promise,' commuters are shown numbly staring out bus windows at night." This, from a recent Rolling Stone article. "Eventually, it's revealed that one of the commuters is nothing more than an animatronic head propped up against the window, where it views and processes what it's witnessing."

There are no electronics, because they are electronic. The commuters have become machines.

"When the android attempts to drift off to sleep," the article continues, "memories and dreams of a crying woman stir it awake. In an unsettling conclusion, it causes the android to have an emotional response to his thoughts. The video ends with the robot head weeping on the bus seat."

According to Rolling Stone, Thom Yorke was partly inspired by how the singer felt he was "living in orbit" while on the long tour in support of The Bends. "The paranoia I felt at the time was much more related to how people related to each other," Yorke said (via).

"But I was using the terminology of technology to express it. Everything I was writing was actually a way of trying to reconnect with other human beings when you're always in transit. That's what I had to write about because that's what was going on, which in itself instilled a kind of loneliness and disconnection."

The severed head means everything now.

I commute to work and navigate most of the city through public transportation - subways and buses mostly. And like the many millions of people around me, I tend to plug in my headphones and checkout. I innocently bump into others, shuffle seats and awkwardly smile at people, but nothing any deeper than that - there is for sure a strong disconnect. Like a severed head.

And like Thom Yorke, this bothers me. A lot. So, a few months back, I stopped. For fifty days straight, instead of listening to a Podcast or some new album, I tried to connect with people.

Then, the strangest thing happened. People began opening up to me and talking about their struggles, their simple thoughts and desires, and their plans for the future. Or, simply, just about life. Suddenly, strangers became people with various stories; they became regular, just like me.

Yorke was trying to reconnect with other human beings who are always in transit, lonely and disconnected. So he made a promise. To stay connected.

But very much unlike computers and very much like people.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Real People : Music

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

Maybe we're alone, or maybe there are billions upon billions of other planets and galaxies and life forms, just waiting to be discovered.

Maybe not.

Either way, "Stay curious."

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Life Questions : TED Talks

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

Every now and again, a seemingly random idea or theme will emerge, in various forms, over a short period of time. I've written about it before. This week, it happened again.

A few days ago, on my way to work, I listened to a podcast from This American Life and instantly had to tell a few Shakespearean fans about it.

Take a few minutes (okay, more like 60) and listen to why Jack Hitt, A Shakespeare enthusiast and critic, who has seen Hamlet a dozen times, staring people like Kevin Kline, Diane Venora (three nights in a row), and "Ingmar Bergman's production done in Brooklyn, performed entirely in Swedish," say "this production was different. Because this is a play about a man pondering a violent crime and its consequences performed by violent criminals living out those consequences. After hanging out with this group of convicted actors for six months, I did discover something. I didn't know anything about Hamlet" (via).

Soon after, and about a month after teaching Hamlet for the first time, I came across this, from Great Big Story.

"According to the prison commissioner, 97% of the people locked up today will someday join us on the outside. Manuel is leaving for a halfway house in 48 hours. He could have been out weeks before but chose to stay in prison so he could finish the play. Hutch has a scheduled date for release. And a few more of the cast have parole board hearings coming up to decide whether they've changed enough and should be allowed to mingle with us on the outside. To that extent, this whole night, including the cast party, is just another rehearsal" (via).

Jack Hitt said he didn't know anything about Hamlet until watching it performed live, in prison. I wonder if he also learned about those living behind bars, those whom society considers only outcasts, criminals, and non-contributors. I wonder if he knew nothing about them too, just like me.

You can read more about Teaching Shakespeare in a Maximum Security Prison or watch some behind the bars footage of prisoners performing Shakespeare.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Real People : Do we not bleed!

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

Aerial photography platform SkyPixel received 27,000 entries to its 2016 competition. Here are the winning shots plus some of The Guardian's favorites.

Published by The Guardian

Wednesday 25 January 2017

A line in the sand ... SkyPixel’s competition was open to both professional and amateur photographers and was split into three categories: Beauty, 360, and Drones in Use. This image – of a camel caravan in the desert – won first prize in the Professional Beauty category.

Photograph: Hanbing Wang/SkyPixel

Dam near perfect ... second prize in the same category was of the Huia Dam in Auckland, New Zealand. Hong Kong-based SkyPixel was launched in 2014.

Photograph: Brendon Dixon/SkyPixel

Dead straight ... this image of a road bridge in the US won first prize in the Amateur Beauty category.

Photograph: SkyPixel

Green waves ... this shot, taken in Italy, won second prize in the Amateur Beauty category.

Photograph: Mauro Pagliai/SkyPixel

ce art ... third prize in the Amateur Beauty category. This image is of a frozen river in the US.

Photograph: SkyPixel

Catching the winning image ... fishermen close the net in Fujian province in China. This was the grand prize winner in the competition.

Photograph: Ge Zheng/Ge Zheng/SkyPixel

On the terraces … the competition – the first run by SkyPixel – attracted 27,000 entries, including this one of a rice terrace in China, which was one of our favourites.

Photograph: SkyPixel

Where did you park the car? Another of our favourites, though not a category winner, is of a huge parking lot.

Photograph: SkyPixel

City cool … people play amid the fountains.

Photograph: SkyPixel

And they were all yellow … uncredited landscape shot.

Photograph: SkyPixel

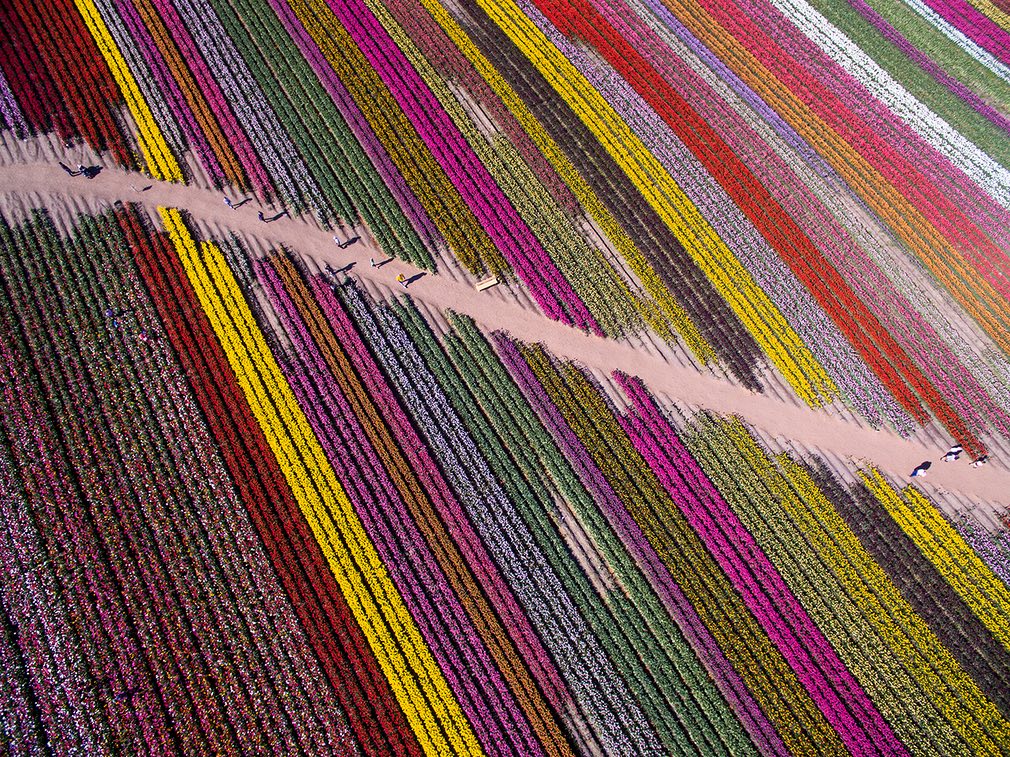

Rainbow lines … a track runs between the multicoloured lines of tulips in the Netherlands.

Photograph: SkyPixel

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : On Living : Critical Thinking

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

Admittedly, I started the below video a few days ago, then turned it off about two minutes in. I was bored.

Then, in the days to follow, I had a few interactions with various colleagues and friends and those brief two minutes kept coming back to me, because it was playing out in real life. So I went back to the video and, although it's a bit . . . dry maybe? I still came away with some key pointers and habits I'd like to fall into.

"Sincere deep connection eludes us" because we don't know how to have conversations - nobody really ever taught us. All too often, "we stay on the surface of events, neglecting how we felt or how it meant to us," because that's easy, and it's safe. Better to be thought boring and put-together than funny, yet a stupid, or a failure - I think we call those kinds of people "fools."

This surface-level type of discussion, though, is often stifling, and lonely, leaving everyone bored and disconnected. Because really, no one is actually says anything, and therefore, no one is truly connecting.

A good conversation is not just about what we say - how vulnerable we are - but even more so on how we listen. "Most of us think we have communicated when we have told someone something," George Bernard Shaw argues, "but {communication} only occurs when someone effectively listens . . . It’s the recipient, not the author" that allows for a deep and meaningful conversation.

The Chinese character for "listen" is a conglomeration of four characters and encompasses this idea.

To listen, to engage fully in a conversation, we need to hear with our ears, our eyes, and our heart, and we need to treat the other person as King - we give them our undivided attention.

Theodore Zeldin, author of Conversation: How Talk Can Change Our Lives, says that conversation "is an adventure in which we agree to cook the world together . . . and make it taste less bitter." True meaningful conversation - where we are open and vulnerable and where the audience is receptive and engaged, and respectful - allows us to connect intellectually, emotionally, and, consequently, personally. It is a place where we are no longer alone, and were we can grow.

"A conversation is a dialogue" says Truman Capote, "Not a monologue," and unfortunately, we have too many monologues and not enough dialogues. One reason for this might be that we are more concerned about sharing our ideas, our thoughts, and our stories than we are about listening to another, than we are about learning. Often, we'd rather teach and be treated like the king, rather than the other way around.

Another reason might be because we're afraid to be wrong.

"If you start a conversation with the assumption that you are right or that you must win, obviously it is difficult to talk." I resonate with this Wendell Berry quote because, if I'm honest, it is often my default. I want people to think I'm smart, that I've read that book or watched that movie or researched that topic - and that I know all about it. Listening with a willingness to be wrong has subjective connotations; it implies an inferiority - of knowledge and personally. And I hate feeling inferior, or worse, an outsider - of knowledge and personally.

But that's the heart of listening. Treating another as more important than self. Because they are the King, and the King deserves our respect, even if I disagree with them. Scratch that. Especially if I disagree with them.

How this looks, though, is difficult to capture because, at least for me, it is a complete conundrum.

In a recent discussion with a colleague (Ed Blanchard), I discovered that whenever I'm engaged with someone, when I am connecting with their thoughts and ideas, I interrupt them - a lot - because I'm all in. My mind is wrestling with the ideas, my heart is pounding and excited, and I want to clarify, to build off whatever is said, and I want to engage - here and now. If I'm quiet, if I'm sitting back and simply staring, more times than not, it's because my mind is somewhere else. My interrupting is because I'm invested.

But when I'm speaking, being interrupted is annoying because I want to be heard. Because my ideas are brilliant, and your breaking up my train of thought (curse you!).

This, as you can probably see, causes problems.

I'm currently engaged in an email discussion with a friend, Warren MacLeod over a book we've both recently read entitled Silence. The email discussion is interesting because, although the pacing is frustrating, it is also enlightening. In an email, I have to to read and reread Warren's thoughts without the pleasure of interrupting them. In turn, my thoughts are a bit more planned out and articulate because I can read and reread what it is I've said. I even put some of my answers on pause, go to the bathroom, get more coffee - whatever - then return to his question and my thoughts (is there a better place for thinking than in a bathroom?). Our conversation then, is patient, and it is extremely purposeful. We say what we want to say and mean what we say. It takes time, but the end product has a depth to it I don't always experience.

This type of conversation can happen in person too, I'm just not good at it. But my wife is, and recently, a friend affirmed her in it, and it convicted me. Her friend told her that recently, when her and her husband asked their middle school aged daughter, "Who do you want to be like when you grow up?" the daughter said, "Mrs. Miller." Why? "Because she looks at me when I talk to her, laughs at my jokes, and cares about what I have to say."

She listens with her eyes, ears, and heart - she treats her like a Queen.

Several years ago, a friend once told me to hold people's memories and stories like an antique, China glass - with extreme care and gentleness. "If you crack it," they said, "likely, they won't let you hold it again." I think the same can also be applied to any conversation, and I think Theodore Zeldin would agree. "The idea of friendship" he argues, "has, over the centuries, changed radically and has created a new pressing issue for humanity, the need for real conversation. It is not new lands we need to be discovering but other people's thoughts."

We live in an age where we can communicate faster and easier than any other time in history, yet, we are still disconnected. We are still alone.

The art of conversation is difficult, but it's vital. More than ever. We need to set down our phones, look people in the eye, and listen. Truly. With our eyes and ears and with hearts that are eager to discover new lands of thoughts and relationships.

We need to have conversation.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : On Living : Critical Thinking

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

I'm not really a movie person. In general, they tend to be too long and I'm too tired because we won't start watching till after the kids go to bed, which means play won't even be pressed till around 8/8:30 and, well, with a bedtime around 9:30, it's a struggle.

Also, after watching a trailer and thinking, "Yes, that looks GREAT!" I forget about them and end up never watching them, or watching them too late. After everyone else has moved on.

I think I'm older than I think I am.

Anyway. Here are a few movies I'm either intrigued enough to stay up the extra hour or so for to give it a good hardy try, or I'm going to brew another pot of coffee for because, damn, it looks good and I have to watch it.

Make Coffee: This is either going to be a knock-down, heart wrenching, artistically brilliant, beauty of a movie, or the complete opposite of that. And I'll be ticked because I'll have wasted good coffee. And I love my coffee.

Intrigued: This seems a bit darker than I normally like, but I'm a sucker for anything portraying brothers as bothers should be - loyal. And this one could be one of those.

Make Coffee: When Owen Wilson plays characters that aren't Owen Wilson, often, they're pretty good. Throw in Julia Roberts and a kid being bullied for being different but overcoming and changing the school and surrounding community . . . coffee please. And some Kleenex.

Intrigued, with coffee on hold: Not because I don't think it will be a fully entertaining movie, in the shallowest sense of the world, but because racial movies make me nervous. Movies that attempt to tackle racial tension, especially when they bring light to a difficult and misunderstood moment in history, are golden. But movies that don't can be horrifically damaging. So, I'm nervous. But also intrigued.

Intrigued: Like movies that portray brothers as brothers should be, I'm also a sucker for any movie where old people figure out life, reconcile with family, and head into their final days with their heart at peace. This could be one of those. Or it could be super cheesy and drastically unrealistic. It might be best to watch this one on a Sunday afternoon so I can end the weekend well, either with a feel-good movie, or a great nap.

Make Two Pots of Coffee: Out of them all, this one seems to be the most sure-fire. To the point that I might not even need coffee for the movie, but for the hour or so afterwards where I'll want to sit and talk or think or write about how powerful and funny and beautiful it was. And then I'll watch it again with friends. And then again with family over Christmas or Thanksgiving. And then again, several years from now when I can quote it and laugh at it and cry with it, even before the scenes and lines come. I'm pretty stoked about this one.

If you have any suggestions, write them in the comments. I'd love to hear it!

I look forward to talking about them, over coffee, preferably before 8:30pm.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Movies : Movie Clips

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!

Recently, and not so recently, I've been wrestling with the difference between critical thinking and criticism because, in and out of the classroom, the seem to have become synonymous. And they shouldn't be.

As in most cases, somebody has done a study on why this is, why we tend to criticize rather than encourage, and, as in most other cases, I disagree with the findings.

Teresa Amiable, director of research for Harvard Business School, says we tend to focus on criticism because of hypercriticism and the idea that when we hear negative statements, we think they’re inherently more intelligent than positive ones (via).

Teresa began exploring hypercriticism back in the 1980s when "she took a group of 55 students, roughly half men, half women, and showed them excerpts from two book reviews printed in an issue of The New York Times. The same reviewer wrote both, but Amabile anonymized them and tweaked the language to produce two versions of each—one positive, one negative. Then she asked the students to evaluate the reviewer’s intelligence" (via).

For the excerpt that was negative, the students thought the author, “definitely smarter" and "more competent," but also “less warm and more cruel, not as nice."

“The brain," according to Prefessor Nass, "handles positive and negative information in different hemispheres," and "Negative emotions generally involve more thinking, and the information is processed more thoroughly than positive ones. Thus, we tend to ruminate more about unpleasant events — and use stronger words to describe them — than happy ones" (via).

Negative emotions involve more thinking, and are processed more thoroughly, which is why they are regarded as higher levels of thinking. It's also why "almost everyone remembers negative things more strongly and in more detail.”

Roy F. Baumeister, a professor of social psychology at Florida State University and co-author of “Bad Is Stronger Than Good,” agrees. “Research" he argues, "over and over again shows this is a basic and wide-ranging principle of psychology," because “It’s in human nature, and there are even signs of it in animals." He did a lot of experimenting with rats and concluded that, “Bad emotions, bad parents and bad feedback have more impact than good ones. Bad impressions and bad stereotypes are quicker to form and more resistant to disconfirmation than good ones.”

Although I resonate with much of Baumeister's findings, his research method also points to the fallibility of the solution. Namely, we're not rats. We're humans, and as such, we are able to reason, discern, and, through sincere analysis, change our habits, and our way of thinking.

We are not creatures of instinct and survival alone. We are extremely complex, and fully human - we are set apart from the animal kingdom.

Yet, the findings are hard to refute, and I find myself nodding along to Professor Amabile's conclusions that "the negative effect of a setback at work on happiness was more than twice as strong as the positive effect of an event that signaled progress. And the power of a setback to increase frustration is over three times as strong as the power of progress to decrease frustration" (via).

Some theorists speculate this mindset, this way of thinking, is evolutionary and beneficial because in the ancestral environment, "focusing on bad news helped you survive" (via).

This is difficult to swallow because, even if it is true, that focusing on bad news helps us survive, I don't think it's what any of us want, to merely survive. We want us to thrive. And constantly pointing out someone's errors and where they could have improved, how they could have said something better, or how their actions (or inactions) were offensive doesn't help anyone to thrive and live and grow. It breaks down and destroys. It creates a culture of disappointment and fear.

A few months ago, while waiting in line to buy some baozi, I noticed the shirt of the woman standing behind me. It was all black with a simple white font that read, "If you reach out and touch the darkness, the darkness will touch you back." When we focus on bad news, when critical thinking becomes synonyms with criticism, we begin to not only reach out and touch the darkness, we embrace it, cling to it, and all to quickly we begin to drown in it - kicking, scratching, and fighting. Surviving.

What would happen if we focused on critical thinking yet pointed out the positives? And I don't mean the "everyone is a hero" or "everyone deserves a trophy" sort of positives, because that isn't critical thinking. It's the complete opposite. That's why it's been so damaging to an entire generation.

To be a critical thinker means spending time with something, dissecting and analyzing something (or someone) and formulating an educated opinion of it (or them). Great movies are, "Critically acclaimed masterpieces" because they've been vetted and the movie critic can give clear and articulate reasons why they loved it, why it was brilliant, and why we, the audience, should spend our time with it. This is very different than the "A for effort" sort of mentality. It's critical and deeply analyzed, and although flawed, it still has plenty to celebrate.

But this also, I think, articulates the difference of positive and negative criticism.

Think back to a time when someone gave you positive criticism, and then when someone gave you negative criticism. Then think of another time. And another.

I bet, if you think through these moments long enough, something like this will emerge.

Over the past ten years of teaching and public speaking, I've had a decent amount of responses from the student or audiences, and it's the negatives that have stuck with me over the months and years that follow, which isn't surprising. Negative experiences tend to do that. Recently, however, I've begun to believe that negative experience carry more weight not simply because they're negative, but in how they are negative. They are more specific.

For example. Last fall, after giving a presentation entitled Stories Matter at the ACSI Teacher Conference, an elderly woman, who sat in the front row with a head of thinning white hair (she reminded me a lot of my grandmother), found me and said, "I loved it. It touched me here (she pointed to her head) and here (and pointed at her heart). Thank you." I was touched, and fully encouraged. But only for a short while because there was nothing specific about it. It was too generic. I know she meant well and truly it meant a lot that she sought me out to say something, but because there was nothing to grab hold of and use and grow on for the next time, it paled in comparison to the person who could articulate with rather acute specifics, where the presentation floundered.

Whenever people criticize, most of the time, it's with specifics. They'll say, "When you said (something), I was offended" or "The way you did (this other thing), it was hurtful" and "When you act like (something else), it's immature. I've never had someone come in and say, "What you said or did was terrible. All of it. Just terrible." They come in with specifics. Things I can hold on to.

But I have had people praise that way. "Thank you," or "You did a really good job, really good" and things of this nature, which is great and I truly do believe they mean well - and it's far better than saying nothing at all. But it leaves me with nothing to hold on to. And when the rain and winds come, I need something strong and concrete to grab hold of. Otherwise, I kick and scratch and scream and try to survive.

Being critical thinkers does not mean we have to be criticizers. But it does mean we have to work hard at changing the way we think. Finding why we disagree or how we're offended has become too easy - its' second nature. But is also touches the darkness. Critically encouraging someone, with detailed and concrete specifics, offers light in a dark world . . . or when all other lights go out (does anyone else having running Lord of the Rings quotes forever in their head?).

Teresa Amiable says we tend to focus on criticism because of hypercriticism and the idea that when we hear negative statements, we think they’re inherently more intelligent than positive ones. I think it's time we holistically disagree with this statement.

We're not rats. We're not animals. We're deeply complex and intelligent humans who can critically analyze situations, make predictions, and act based on intelligence, not instinct. And our goal is not mere to survive, but to thrive.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : On Humanity : On Living

BE SURE TO SCROLL DOWN AND SUBSCRIBE - THANKS FOR READING!