The students knew “G” was going to lose it eventually because they knew him, and because he’d been brewing ever since the first week of school. But I didn’t. I was new to the district and didn’t know “G” from Adam. So when he yelled, “Man, Fuck this shit!” and slammed his book shut, I was a more than a bit stunned. When I told him to sit back down, he refused, saying, “This is bullshit!” and walked out the door.

We were in the throws of reading “The Crucible” and just about to read one of my favorite scenes, so instead of following “G” out the door, I smiled and I asked them to continue on. “G” could wait.

A few minutes later, the bell rang and I went to the principal’s office and asked for “G” to not be suspended or get detention. Instead, I asked that he be allowed to spend the next week eating lunch with me.

“Why?” she asked.

“Because of my father,” I responded.

Growing up, I often heard stories of how biblical shepherds handled sheep that constantly strayed – they would break the sheep’s legs.

Then, because the sheep could no longer walk, the shepherd would carry it on his shoulders until it healed. During this time, a bond of trust would form between the shepherd and the sheep. Once healed, the sheep would no longer leave the shepherd.

So, when my mother told me not to borrow her bike and I did anyway, she tried to break my legs.

My bike was fine, but hers was better, and the road to my friend’s house was long. So long in fact that it took thirty minutes for her to catch up in the car. It took her less than three minutes to bolt from the car, stuff her bike into the undersized trunk, yell, “WALK HOME!” and whip the car around and through the oncoming traffic.

By the time I made it back to the house, the cool of the evening was beginning to settle in and I had some pretty fantastic excuses worked out.

I walked through the front door, parched, and ready to wash myself of blame and trouble. She too was ready, “Go to your room,” she said, “Wait for your dad to come home.” When she didn’t glance up from her floured tabletop and rolled out dough, I knew I was in trouble.

The hours between then and my dad’s pickup bouncing over the curb were forever. The hour it took for my father to slowly open the door and sit on my bed was even longer. The talk, however, was less than a minute: “No TV, no friends, no phone, for two weeks.”

“TWO WEEKS!” I yelled.

“Yes, two weeks,” my dad said, even though it was summer, beautiful summer, when kids should be out with their friends, riding bikes, fishing in small ponds, building forts, and getting into simple mischief.

But that wasn’t the worst of it. Not only was I confined to the acre and a half of my parents’ property, I was to memorize Bible verses, read books on the Lord’s second coming, and “think about what I’d done.”

Taking the bike was the “straw that broke the camel’s back,” because it was just one of a hundred times I was disrespectful, disobedient, and selfish, and I needed to learn my lesson. I needed to have my legs broken.

As a child, my mother didn’t yell and scream when I misbehaved, but she did place the responsibility for punishing a disobedient and defiant young boy upon his father. She had a hand in creating the consequence, but he was the one who enforced it, who sat with me in my anger and tears. He was the one who talked me through it, who listened to my weak negations, and who patiently, with tears in his own eyes, refused to budge or relent but affirmed that I would indeed be grounded for two weeks.

He was also the one who took me fishing.

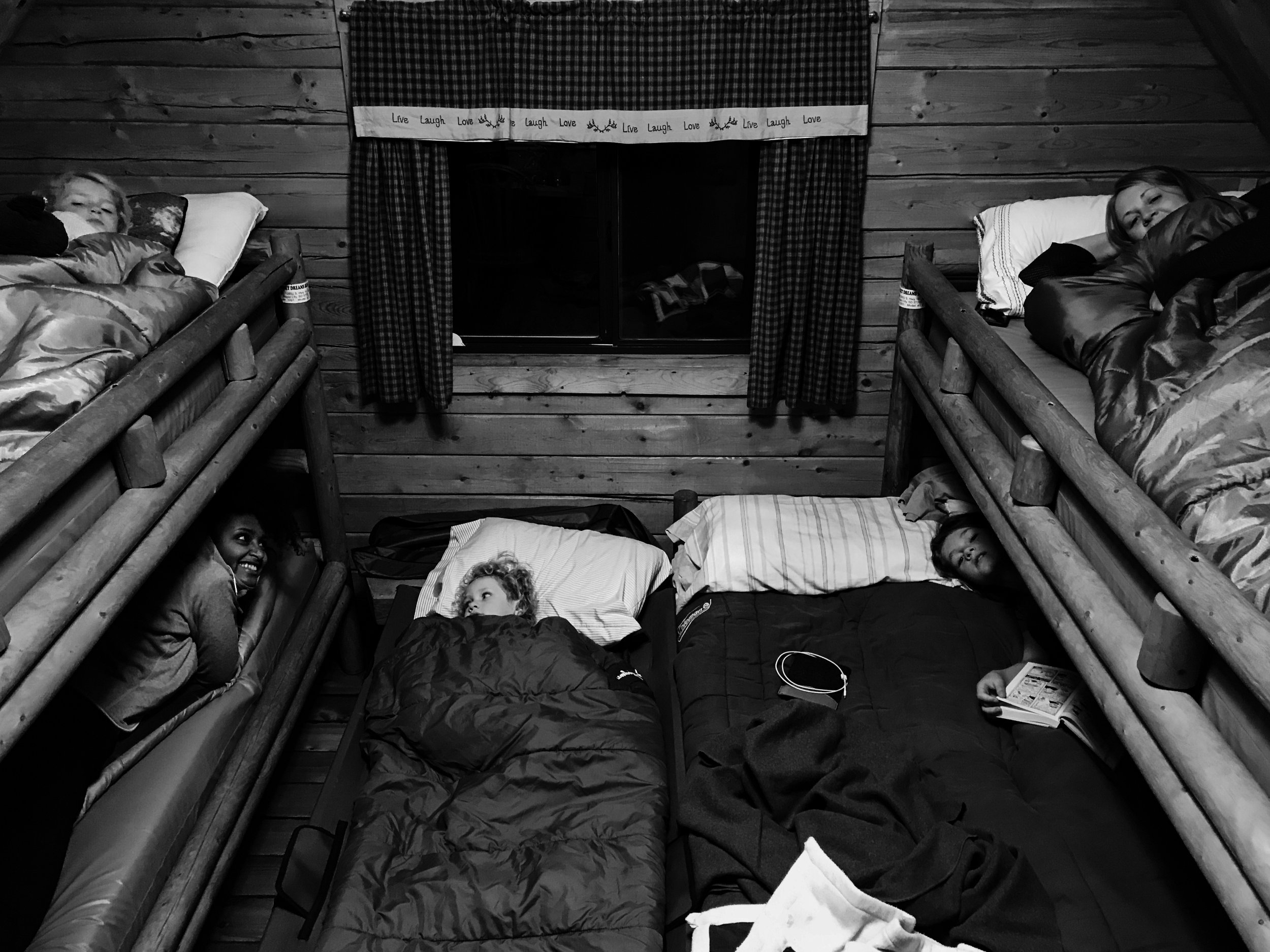

About a week into my grounding, I was sitting in the backyard, reading, when my father came home from work and asked if I wanted to go to the river for the next week. I still had to read and memorize, but I could do it from the camper, after running bank lines and trotlines and swimming in the great currents of the northern Mississippi River. “Of course!” I yelled.

“Great,” he said, “then pack up your stuff. We’ll head out early tomorrow morning.”

I slammed my book shut and ran inside the house; my dad grabbed the tackle box and lifted me to his shoulders, just like a good shepherd should.

The next morning, we left early.

The five-hour drive to the campground was spent hearing the same old stories of when my dad was a kid on the river. How he and his friend caught a huge snapping turtle with only a net, how he spent a summer shingling the roof of his parent’s cabin, and about the time he and his friend built a bonfire so massive that it caught the attention of a barge passing by. He told me about the propane tank.

It was he and his friend’s first night away from the cabin and they were a bit scared of the dark, even though neither one would admitted it, so they threw log after log upon the roaring flames. When they found the tank buried beneath a pile of driftwood, they threw that on too. Then quickly forgot all about it.

Minutes later, it exploded, sending sparks and wood and teenage boys flying in all directions. No one was hurt and Dad chuckled as he told it, just like he’d done the dozen or so times before, which made me laugh and smile too because I loved that story.

Then, we were there. As we crested the bluff, my dad stopped, “Oh no.”

“What?” I asked.

“It’s flooded.”

The river must have just recently receded back to its normal levels because the road was covered with a layer of deep, sloppy, river mud. “Well,” my dad said, slowly pulling forward, “if it doesn’t rain the rest of the time we’re here, we should be okay.

With each nightly downpour, our fear that we’d never make it out grew, and with each passing day, my dad prepared to get us out of the mess and safely home by shoveling as much mud off the road as possible then haul and spread gravel from a nearby gravel pit over the road, all without a shovel.

And never once did I doubt that he could, that he would, and that we wouldn’t make it home safe.

But then, a prison work crew showed up to fix all the picnic tables. When they paused for a quick lunch break, my dad asked one of them if he wanted some of our fish. The man looked at my dad and said, “You better as’ the boss firs’.”

“I did,” my dad replied, holding up the plate of freshly grilled catfish, “he said it’s okay.” The man looked around, at his other inmates, the river, then back to the plate, “Well,” he said, “You got any salt?”

Over the next thirty minutes or so, the dozen or so inmates finished off all the fish we’d caught the previous four days. I watched from the camper, hidden behind my book, but reading nothing. One man, with his mouth full, shook his head, “Shit. Dis is better ‘en my chicken,” and I knew he was telling the truth because my dad grew up on the Mississippi river, fishing, working, and learning from his parents, and he knew how to grill catfish.

Before leaving, the crew grated the road for us, laid down new gravel, and lined the old picnic tabletops under our camper and van. When it rained hard on our last night by the river, my dad slept soundly. In the morning, instead of clearing the road or heading home, we went fishing and my dad told stories of when he was a young and imperfect son.

My dad didn’t have to break my legs for me to learn how to trust him. Nor did he have to yell and scream and rain down punishments for me to respect him. He just needed time with me, to take an interest in me, and to show me that he just because my behavior was inappropriate it didn’t mean I wasn’t wanted, or loved.

Instead of creating consequences, he created memories. And in the following years, whenever I would get into trouble or found myself stuck, it was my father I went to, who I met for coffee or called on the phone while wandering the dark streets, searching for answers. Because he was the one who took me fishing.

So when “G” said, “Fuck this shit!” in front of the entire class, when he jumped up from his chair and started walking out of the room yelling, “this is bullshit!” I didn’t walk him to the office or write him up or chase him down the hall, yelling and screaming and threatening detention, suspension, or failure of the class. Instead, I let him go and thought about fishing with my father. When the bell rang, I went to principal because, like me, “G” didn’t need to have his legs broken. Nor did he need me to carry him. He just needed someone who’d be willing to sit with him, in the muck and the mire, and hear his story.

“I want “G” to spend the next week with me, during lunch,” I said, “Is that possible?” She was a bit skeptical.

“Please. Don’t write him up, just let me spend time with him.” And because I’m fortunate to have supportive bosses, she said okay.

The next day, with a ham and cheese sandwich and a few freshly cut vegetables scattered on my desk, I waited for “G” to show, but he never did. When I saw him in the hallway, I asked him about it, told him he wasn’t in trouble, but that I just wanted to talk and hang out with him for a bit. He said he’d come tomorrow.

When he showed up, I asked him how he’s doing. “Not good,” he said. Then, he told me about his family.

“My dad came in my room and asked where Mom is” he says, lounging in the cold desk, arms crossed, “and I didn’t know if I should tell him or not. Next thing you know, we’re sitting in the car for three hours. I call my mom and she says she’s at the movies but there aren’t any cars in the parking lot because there isn’t any movie showing. My dad starts crying and my little brother starts crying and I’m thinking, ‘What’s going to happen?’ Mom didn’t get home till 3am.”

“I’m sorry,” I say, knowing where this was going. He looks up.

“Hearing your parents argue is the worst. Having your ten-year old brother cry in your arms isn’t what anyone wants.”

He fights back tears. Because he’s tough.

“Mom’s crying, Dad leaves, and nobody knows where he went. Three days pass and no sign of my dad nowhere. Until the Fourth of July.”

The bell rings and “G” gets ready to go to class. “Thanks,” I say, “Thanks for sharing.” He nods gently and heads to class.

The next day, and for the four days after, he comes back.

He tells me how his parents almost got back together, but then, on a trip to the beach, they got into another big fight and he, his little brother, and his mom had to walk home in the rain. He talks about how she eventually moved out and how difficult it was because she still lived in town, with another woman.

He tells me that was when he finally broke down and cried because the next morning, when he woke up, he found his dad passed out on the couch, “No one should have to experience this,” he says.

“G” used to be a “good kid,” a star athlete, and a decent student. Now, he doesn’t understand why he is so angry all the time, why he can’t control his temper.

“I used to be that kid thinking life would be so easy. But that just makes it harder.”

We sit in silence for a minute.

“I just want to beak down and cry,” he says “but it’s too late to be crying over something that I can’t fix. Life isn’t easy, and it never gonna be.”

“I’m sorry,” I say again, thinking of my dad and the river and wondering if and how I could lift “G” to my shoulders, because so much of his life seems bent on breaking his legs.

The bell rings, and I still don’t know what to do.

Later that day, another teacher writes “G” up and doesn’t want him in their class because he’s disrespectful and curses and needs to be taught a lesson.

He asks if he could spend his detention with me.

A week later, when he needs help with credit recovery for science class, he comes in during lunch and we work through the material together – neither of us having a clue what is being asked but finding, and sometimes guessing, the answers together.

Later in the quarter, he writes a poem about how the Fourth of July used to be the best time of year, until Mom and Dad argue, a little brother cries, and a family falls apart, and I find myself trying to fight back tears, to be tough like “G”.

Then he writes a powerful short story about his parent’s, his mother, and the day he found out she was leaving her family – her “G” - for a woman she met at work. He writes an essay on the power of music and another on anger and how it fuels his life but ruins his days, and I smile.

“G” hasn’t stopped cursing in class, but he is trying, he is showing up almost every day, and he is working on what he can – even if it might be “bullshit”, and that makes me smile. Because that means he’s healing.

I know I’m not “G”’s father or his shepherd, but I am his teacher. And when we had lunch together, when he told me about his life and the things that matter most, I listened. When he asked me if I could relate, I told him about my failures as a son, a father, a teacher, and a husband. I told him he wasn’t alone, in his failure or his pain.

I wasn’t able to take “G” fishing or carry him on my shoulders, but I do think I was still able to help him heal, if only a little, because whenever I walk home from work and a car honks and honks and honks, I know it’s “G”, driving with his girl, just wanting to say hi.

And sometimes, it’s the best part of the day.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : On Education : On Parenting