I thought this book was going to be about more than what it was, but I still found it worth reading because, if nothing else, it raised some pretty provocative thoughts and questions. And any book that can do that at least once is worth reading, at least once.

Here are some of the highlights:

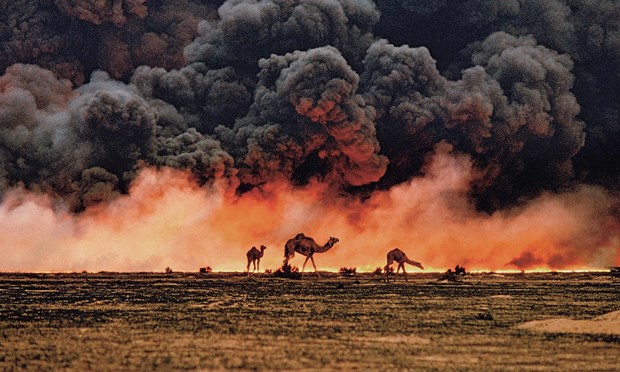

The photographs are a means of making “real” (or “more real”) matters that the privileged and the merely safe might prefer to ignore (pg 7).

This reminded me of Jacob Riis and his revolutionary work, "How the Other Half Live" which exposed the rich and privileged to the reality of how many lower income families lived. His work is largely credited with the reform in child labour laws and opening the door to a new way of thinking about the world - Realism.

We are not monsters, we members of the educated class. Our failure is one of imagination, of empathy; we have failed to hold this reality in mind (pg 8).

This sentiment struck a cord with me because it doesn't simply apply to financial status, but all. To those who are emotionally wealthy, to those who are physically or mentally healthy, political or religious it doesn't matter. Those who have find it difficult, at times, to imagine a life that does not.

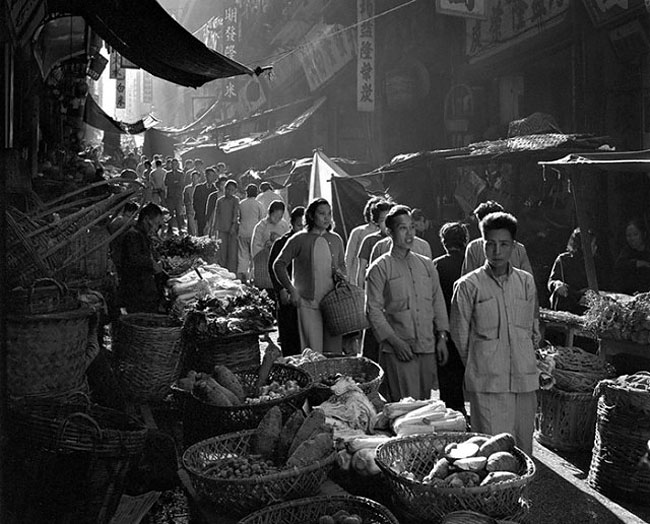

In contrast to a written account – which, depending on its complexity of thought, reference, and vocabulary, is pitched at a larger or smaller readership – a photograph has only one language and is destined potentially for all (pg 20).

The slight of hand allows photographs to be both objective record and personal testimony, both a faithful copy or transcription of an actual moment of reality and an interpretation of that reality – a feat literature has long aspired to, but could never attain in this literal sense (pg 26).

This might apply to most writers, but whenever I ask my students to draw what they see in "The Red Wheelbarrow" by William Carlos Williams, they all draw - almost to perfection - the exact same thing. It doesn't matter the age, the ethnicity, the location, or anything else, it's all the same. And that's pretty amazing.

Photography is the only major art in which professional training and years of experience do not confer an insuperable advantage over the untrained and inexperienced - this for many reasons, among them that large role that chance (or luck) plays in the taking of pictures, and the bias toward the spontaneous, the rough, the imperfect. (There is no comparable level playing field in literature, where virtually nothing owes to chance or luck and where refinement of language usually incurs no penalty; or in the performing arts, where genuine achievement is unattainable without exhaustive training and daily practice; or in filmmaking, which is not guided to any significant degree by the anti-art prejudices of much of contemporary art photography) – pg 28,29

This is perhaps the single most reason why photography is so popular, but also why it is so difficult. Anyone can take a good shot once or perhaps just a few times, but to capture the moment, the mood, or the spirit of a moment time and time again takes experience and expertise. Just like any other art form.

What does it mean to protest suffering, as distinct from acknowledge it?

I don't know, but that's a great question. I'll have to think more on it.

But surely the wounded Taliban soldier begging for his life whose fate was pictured prominently in The New York Times also had a wife, children, parents, sisters and brothers, some of whom may one day come across the three color photographs of their husband, father, son, brother being slaughtered – if they have not already seen them (pg 73).

This quote really struck me. Because it's right. How often do I see the death and suffering of people all over the world and forget, especially in times of conflict, that they too are fathers, sons, brothers, and friends. That they too will have people weeping over the loss of life. That they too are just as human.

For photographs to accuse, and possibly to alter conduct, they must shock” (pg 81). Yet, “Shock can become familiar. Shock can wear off (pg 82).

Which then begs for more provocative, more shocking photographs, which dulls us even more. The question here that isn't asked but should be is how long will this cycle continue before we no longer feel shock at all? Before all suffering and abuse is simply familiar?

And what can we do to fight against it?

Resources:

- Tennyson, “The Charge of the Light Brigade”

- Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, by Walker Evans

- Kazuo Hara’s, The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On

To Consider:

- The planting of the American flag on Iwo Jima on February 23, 1945 by photographer Joe Rosenthal was reenacted. It was staged. Is this okay? For the purpose it was wanting to serve, was it okay to reproduce an event? It has inspired thousands and has become an iconic moment and image of American history . . . does that fact that it isn't completely authentic in time and space make it any less relevant or powerful of a moment? Of what it symbolizes?

- How could church going citizens create and use postcards that depict lynched and murdered African American men and woman? But even before that, how could church going citizens LYNCH AFRICAN AMERICAN MEN AND WOMAN?!?!? And how can they/we still do it today?

What will people be saying of us, in just a few short years from now?

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Reading Log 2017 : Reading Log 2018