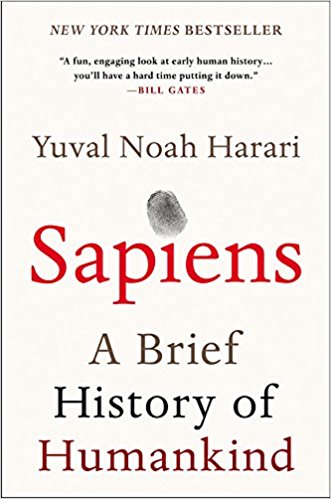

Cannot recommend this book enough, even though for us slow readers, it's quite the undertaking. However, for all the pains and troubles and time, it's fully worth it.

Not only does Harari somehow manage to capture the entire scope of human history in an engaging and challenging sort of way, he also aptly and continually finds ways to challenge our current mindset and norms of life and living and understanding. He's brilliant!

Sapiens is one of those must-read books that will linger in its readers mind long after it has been placed on the shelf, only to be passed around or reached for time and time again. If only just to refresh our memory.

Here are a few highlights:

Most top predators of the planet are majestic creatures. Millions of years of dominion have filled them with self-confidence. Sapiens by contrast is more like a banana republic dictator. Having so recently been one of the underdogs of the savannah, we are full of fears and anxieties over our position, which makes us doubly cruel and dangerous. Many historical calamities, from deadly wars to ecological catastrophes, have resulted from this over-hasty jump (pg 12).

Rather than heralding a new era of easy living, the Agricultural Revolution left farmers with lives generally more difficult and less satisfying than those of foragers. Hunter-gatherers spent their time in more stimulating and varied ways, and were less in danger of starvation and disease. The Agricultural Revolution certainly enlarged the sum total of food at the disposal of humankind, but the extra food did not translate into e better diet or more leisure. Rather, it translated into population explosions and pampered elites. The average farmer worked harder than the average forager, and got a worse diet in return. The Agricultural Revolution was history’s biggest fraud (pg 79).

One of history’s few iron laws is that luxuries tend to become necessities and to spawn new obligations. Once people get used to a certain luxury, they take it for granted. Then they begin to count on it. Finally, they reach a point where they can’t live without it (pg 87).

Ted Kaczynski actually said something very similar in his Manifesto:

Another reason why technology is such a powerful social force is that, within the context of a given society, technological progress marches in only one direction; it can never be reversed. Once a technical innovation has been introduced, people usually become dependent on it, so that they can never again do without it, unless it is replaced by some still more advanced innovation. Not only do people become dependent as individuals on a new item of technology, but, even more, the system as a whole becomes dependent on it . . .Thus the system can move in only one direction, toward greater technologization. Technology repeatedly forces freedom to take a step back, but technology can never take a step back—short of the overthrow of the whole technological system.

Interesting. Might have to consider that a bit longer.

Back in the snail-mail era, people usually only wrote letters when they had something important to relate. Rather than writing the first thing that came into their heads, they considered carefully what they wanted to say and how to phrase it. They expected to receive a similarly considered answer. Most people wrote and received no more than a handful of letters a month and seldom felt compelled to reply immediately. Today I receive dozens of emails each day, all from people who expect a prompt reply. We thought we were saving time; instead we revved up the treadmill of life to ten times its former speed and made our days more anxious and agitated (pg 88).

How do you cause people to believe in an imagined order such as Christianity, democracy, or capitalism? First, you never admit that the order is imagined. You always insist that the order sustaining society is an objective reality created by the great gods or by the laws of nature. People are unequal, not because Hammurabi said so, but because Enlil and Marduk decreed it. People are equal, not because Thomas Jefferson said so, but because God created them that way. Free markets are the best economic system, not because Adam Smith said so, but because these are the immutable laws of nature (pg 113).

In order to establish such complex organizations, it’s necessary to convince many strangers to cooperate with one another . . . There is no way out of the imagined order. When we break down our prison walls and run toward freedom, we are in fact running into the more spacious exercise yard of a bigger prison (pg 118).

This next quote might be the most disturbing. Growing up in a Christian home and attending church most of my life, I've always heard of the persecution of Christians from the non-believing world. Not how much we've killed ourselves.

In the 300 years from the crucifixion of Christ to the conversion of Emperor Constantine, polytheistic Roman emperors initiated no more than four general persecutions of Christians. Local administrators and governors incited some anti-Christian violence of their own. Still, if we combine all the victims of all these persecutions, it turns out that in these three centuries, the polytheistic Romans killed no more than a few thousand Christians. In contrast, over the course of the next 1,500 years, Christians slaughtered Christians by the millions to defend slightly different interpretations of the religion of love and compassion . . . On 23 August 1572, French Catholics who stressed the importance of good deeds attached communities of French Protestants who highlighted God’s love for humankind. In this attack, the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, between 5,000 and 10,000 Protestants were slaughtered in less than twenty-four hours. When the pope in Rome heard the news from France, he was so overcome by joy that he organized festive prayers to celebrate the occasion and commissioned Giorgio Vasari to decorate one of the Vatican’s room with a fresco of the massacre (the room is currently off-limits to visitors). More Christians were killed by fellow Christians in those twenty-four hours than by the polytheistic Roman Empire throughout its entire existence (pg 216).

There is poetic justice in the fact that a quarter of the world, and two of its seven continents, are named after a little-unknown Italian whose sole claim to fame is that he had the courage to say, “We don’t know” (pg 288).

Strange. That there might be a downside to curiosity. What are the ramifications/consequences of pursing understanding or insight? What (or who) are we killing off? What are we losing?

Just as the Atlantic slave trade did not stem from hatred towards Africans, so the modern animal industry is not motivated by animosity. Again, it is fueled by indifference. Most people who produce and consume eggs, milk and meat rarely stop to think about the fate of the chickens, cows or pigs whose flesh and emissions they are eating. Those who do think often argue that such animals are really little different from machines, devoid of sensations and emotions, incapable of suffering. Ironically, the same scientific disciplines which shape our milk machines and egg machines have lately demonstrated beyond reasonable doubt that mammals and birds have a complex sensory and emotional make-up. The not only feel physical pain, but can also suffer from emotional distress (pg 343).

Each year the US population spends more money on diets than the amount needed to feed all the hungry people in the rest of the world. Obesity is a double victory for consumerism. Instead of eating little, which will lead to economic contraction, people eat too much and then buy diet products – contributing to economic growth twice over (pg 349).

As long as my personal narrative is in line with the narratives of the people around me, I can convince myself that my life is meaningful, and find happiness in that conviction . . . commercials urge us to “Just Dot It!” Action films, stage dramas, soap operas, novels, and catchy pop songs indoctrinate us constantly,: “be true to yourself”, “Listen to yourself”, “Follow your heart”. Jean-Jacquess Rousseau states this view most classically: “What I feel to be good – is good. What I feel to be bad – is bad.”

People who have been raised from infancy on a diet of such slogans are prone to believe that happiness is a subjective feeling and that each individual best knows whether she is happy or miserable. Yet this view is unique to liberalism. Most religions and ideologies throughout history stated that there are objective yardsticks for goodness and beauty, and for how things ought to be. They were suspicious of the feelings and preferences of the ordinary person. At the entrance of the temple of Apollo at Delphi, pilgrims were greeted by the inscription: “Know thyself!” The implication was that the average person is ignorant of his true self, and is therefore likely to be ignorant of true happiness. Freud would probably (392, 393).

So much to chew on. So much to consider. Just as a good book should be.

For more on . . .