If you look closely, you’ll find the characteristic shadows, the armor, the weapons, and the portraits that make Karl’s work his own. And more than that, you’ll find a composition full of many, many moments.

For more on . . .

ideas : People : stories.

the Human Being stuff

If you look closely, you’ll find the characteristic shadows, the armor, the weapons, and the portraits that make Karl’s work his own. And more than that, you’ll find a composition full of many, many moments.

For more on . . .

“The death of one man is a tragedy. The death of a million is a statistic.”

- Joseph Stallin

Most of us know that 3,000 people died on 9/11, but how many Americans know how many Katrina victims there were, or how many people died in the American Revolution. Did the Christian Crusades kill 100 times as many people as the Vietnam War? Or were they identical in their death tolls? Given how much we talk about historical human tragedies, it seems like something we should have a better handle on (via).

Tim Urban, from the popular website, waitbutwhy then goes on to show just how depict the numbers of people killed in hurricane Katrina, the Syrian War, and those killed in the Sichuan 2008 earthquake. He compares most all major wars, world wide car accidents per year, and The Black Death.

All in all, there are a lot of deaths.

And the numbers, when considering that they are people, that they are husbands, mothers, moms and dads, sons and daughters, that they are friends and neighbors and people who had names and lives, becomes so overwhelming that they are no longer relatable.

How can I even comprehend 200 million lives lost?

I can’t. But I can see J.F.K. riding in his car, his desperate wife holding his lifeless body, and I can hear his grainy voice as he addresses the nation.

Does that make me callous? Heartless?

Does that make Stalin right?

“We do a pretty good job of distracting ourselves from the whole ‘I’m gonna die one day’ thing” by distancing ourselves from the personal deaths - “That wouldn’t happen to me.” But we distance ourselves from the global, much closer to reality deaths (natural disasters, car accidents, etc) by seeing the casualties as numbers, not people.

For more on . . .

Love this video.

Its easy to get lost in the art and lose his words, but listen carefully. His process of creating is inspiring, and encouraging.

“I had no idea what this animation would be when I started, and that’s really my big tip. If you’re ever feeling stuck or blank creatively, take a step into the unknown and start doing something . . . until it starts your interest or sparks an idea, and then build on that.”

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Inspiration : Art

Image from Bored Panda

Recently a 33-year-old swimmer and fitness expert, Ross Edgley, returned from an epic 1,780-mile (2,800 km) journey. Ross spent 5 months at sea and is believed to be the first person to swim around the island of Great Britain.

Image from Bored Panda

The fact that this deed was perceived as impossible inspired Ross to be one to accomplish it. “I’ve always been fascinated by British explorers and it was Captain Matthew Webb [first person the swim the English Channel], who really inspired me.

Image from Bored Panda

During this victorious swim, Ross broke 4 world records. The records include – the first person to swim the entire South Coast of the UK, the longest ever staged sea swim, the fastest person on the planet to swim from Land’s End to John O’Groats, and the first person to swim around Great Britain.

Image from Bored Panda

“The biggest challenge now is learning to walk again! My biggest fear when I was coming out of the water and back onto the beach was that I was going to fall over. As I’ve not stepped foot on land for over five months, the tendons and ligaments in my feet have been asleep, so I basically have to learn to walk again. But in terms of bigger thinking, and I know this will sound weird, but I’m still not bored of swimming. A few big swims have been mentioned and this is probably the most ‘swim-fit’ I’ll ever be, so who knows?”

For the complete story and more pictures, visit Bored Panda.

For more on . . .

Photo by @davideragusa

It happened again. This time, in Thousand Oaks, California. You and I both know how the days and weeks to will play out.

“Our thoughts and prayers go out to . . .” we will hear whispered from podiums, while “Enough is enough” banners are posted on websites, blogs, and social media. And for a brief, brief moment, the country will be unified in grief, shock, and horror of what our country has become. Then someone will point the finger of blame. Then another. Then another. Until everyone is pointing, shouting, and condemning, calling for reform, calling for justice, and demanding someone does something to stop this madness.

All the while, someone somewhere will have made a plan, written a note, or posted a video. Right under our tear-stained cheeks and upturned noses. Just like they did in Columbine, almost 20 years ago.

“Eric Harris was a psychopath,” David Cullen concludes in his New York Times bestseller, Columbine, “he was a narcissist, he was a sadists. He wasn’t out to bully bullies, he was out to hurt the people he looked down upon . . . humans.” He wanted to destroy everyone, all of us. Yet fortunately, he only made it to thirteen. He had planned for many more.

According to the investigation that followed Columbine, Eric Harris wanted to go down as a legend. He wanted to make a mark bigger than the Oklahoma City bombings and he wanted to be remembered forever. So he planted bombs in the park on the other side of town, set to go off as a diversion for the cops. Luckily, they didn’t. Neither did the propane tanks in the cafeteria (which would have killed hundreds) nor the bombs in his and Dylan’s cars (which were set to detonate after the police and paramedics arrived, killing them too). In fact, Eric and Dylan never intended to enter the school. Their plan was to wait outside and pick off the surviving few as they fled the carnage of Columbine.

But things didn’t go according to Eric’s plan, hardly anything in fact, except for one seemingly minor detail: the media was there, and they granted Eric Harris his deepest dying wish. He became famous.

Dave Cullen, an author and elite journalist, was “one of the first reporters on the scene” at Columbine. He then spent the next ten years writing Columbine, which is “widely recognized as the definitive account” of the school’s massacre, and for many of the 300-plus pages of his heart-wrenching book, Cullen spends a great deal of time talking about who Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold were, what happened in the days prior, during, and after the infamous shooting, and how people from across the country responded.

But that’s not why he wrote the book. He wrote it because he was trying to figure out why Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold did it. Once answered, he concludes his book with the most important takeaway of his journey: how to prevent this from ever happening again, and who is responsible.

His findings are not extenuating.

Dave Cullen’s conclusion of who is responsible for Columbine and every shooting and massacre is not a familiar one, nor is it a popular, but it is the most accurate and reliable one.

The answer of who is responsible, according to Cullen, is us. We are responsible. Malcolm Gladwell says the same, but where Gladwell fails to provide a solution, Cullen does. It is us. We are the solution.

Let me explain. Or rather, let Cullen explain.

Almost 100% of the time, the perpetrator of mass killings is male, and “{f}or his glorious week,” Cullen explains, “the spectacle killer is the hottest star on earth. He dwarfs any sports champ, movie star, president, or pope . . . They spill a little blood, {and} the whole world knows who they are . . . His face splashed across every screen, his name across the lips of every person on the planet, all in the course of one day. Seems the more people you kill, the more you’re in the limelight.”

So, “If you’re planning a spectacle murder,” Dave Cullen once told a CNN anchor, “here’s what you do:

{There are} two routes to the elite club with the star treatment: body count, or creativity. Choose body count, and you’ve got to break the top ten. The media loves scorekeeping and will herald your achievements with a banner beneath the victims as they grieve. For creatives, go for originality and horror . . . Maximize the savage nature. Make us fear movies theaters, or churches or {school} - and a Joker costume at a Batman movie takes theatrics literally. Live TV was a great twist - only took two victims in Roanoke to get the big-star treatment. Surprise us.

The anchor was justifiably horrified, but that was the point. “These are the tactics the killers have turned on us so callously,” Cullen writes, “They cracked the media code. Easily.” And if the media care about ending this, “we in the media need to see our role as clearly as the perps have. We did not start this, nor have we pulled any triggers. But the killers have made us reliable partners. We supply the audience, they provide the show” (pg 380).

In these few short paragraphs, Cullen models the role we all need to take after events such as these occur: point the finger at ourselves, find where we are responsible, and take ownership of it. Just like Andy Dufresne.

Like everyone else, my favorite scene in Shawshank Redemption is the one where Andy Dufresne emerges from the septic tanking, raises his hands to the air, and is finally free from the deathly Shawshank prison. But it wasn’t until I read those lines from Cullen that I understood why I love that scene, and how Andy Dufresne was able to get there.

Throughout the first half of the movie, the audience is left in the dark as to Andy’s involvement with his wife’s murder. There’s that scene in the beginning, of him stumbling from his car, drunk, and carrying a gun, but nothing more. He adamantly denies killing his wife, but we are never fully convinced of his innocence. Till we hear the story of Elmo Blatch, an old cellmate of Tommy’s, and then our suspicions are confirmed, Andy Dufresne is completely innocent and absolved from the murder of his wife. Somehow, though, that isn’t enough. The movie isn’t entitled Shawshank Absolvement, it is Shawshank Redemption, and Andy is not yet redeemed. That comes later, after Tommy has been killed and Andy beaten, placed into solitude for calling the warden “obtuse”, and at the brink of ruin. And like Cullen, as he comes to grip with the harsh reality of what has happened and who is to blame, his hammer of judgement falls to no one else but himself.

“I killed her Red,” Andy he says with a dull sincerity to Morgan Freeman as they sit in the yard, leaning against the giant stone wall, locked in Shawshank Redemption. “I didn’t pull the trigger but I drove her away. And that’s why she died, because of me.”

Red leans down and sits on his heals, “That doesn’t make you a murderer,” he counters, and he’s right. But so is Andy. He didn’t pull the trigger, but he did play a part. A small part perhaps, or at the very least a forgivable part (no on goes to prison for being a bad husband), but a part none the less. And once Andy is finally able to see that, he is able to admit it. And once he admits it, Shawshank could no longer contain him. He is free.

A few scenes later, he climbs into a sewage pipe and crawls to redemption.

“We did not start this, nor have we pulled any triggers”, Cullen admits, echoing Red’s “That doesn’t make you a murderer.” But Cullen, like Andy, isn’t content with being absolved. He wants freedom. Freedom from a grey and deathly prison, freedom from guilt and shame, and freedom from fear that this will indeed happen again. So he accepts his portion of the blame, “we supply the audience, they provide the show.” He acknowledges his responsibility and admits his complicit role. Then, like Andy Dufresne, he climbs into the sewage pipe and beckons us to do the same.

We, on the other hand, continue to sit in horror and amazement, waiting for someone to unlock the cell.

“For the past few years,” Jason Kottke writes, “whenever a mass shooting occurs in the US that gets wide press coverage, the satirical news site The Onion runs an article with this headline written by Jason Roeder: ‘“No Way To Prevent This,”’ Says Only Nation Where This Regularly Happens’.”

After each mass shooting, our nation raises its hands in grief and disbelief, “How does this keep happening?” Then, because there is never a clear answer, we quickly defend ourselves, our beliefs, and our rights, leaving many people absolved, very few freed, and even fewer redeemed.

There are two definitions offered for redeemed:

the action of saving or being saved from sin, error, or evil.

the action of regaining or gaining possession of something in exchange for payment, or clearing a debt.

Both require an admittance. Both require action. Neither point to someone or something else.

I, like the rest of our country, desperately long for these headlines to be eradicated from our headlines. I’ve also been convicted by Cullen and Andy and believe that casting the blame onto others will only perpetuate the acts. But because I’m not a journalist, I cannot rest with Cullen’s admittance. I must find my own, as an educator.

So far, I’ve come up with three.

“Education is inherently selfish” I found myself saying to a room full of educators, “we spend so much time and effort convincing kids to pursue school and grades so they can better themselves and their future” I said, “we encourage them to follow their dreams and be whatever they want to be, but for what purpose?” I found myself trying not to look at a particular school that has geared their entire program around personalized learning and a system that focuses on each kid as an individual, that teaches each kid to learn at their own pace, in their own way, completely isolated from their peers.

Why school? Why do kids have to go? And why do they have to take the classes that they do? A school I once taught for attempted to answer that question with a giant poster that hung in the hallway for each student and teacher to read. “Do it for you,” and it bothered me every single day.

Is that why kids need to be in school? So that they can go to college, get a nice job, and buy nice things? Or is it so that they can collect experiences and enjoy life? So they can learn how to “Follow their heart”? If so, no wonder they’re miserable.

After they’ve pursued every relationship, dating the hottest boy or girl they can find, after they’ve driven the coolest car, bought the the newest technology, and worn the nicest clothes, what next? After sex, popularity, success, and whatever else their hearts desire. what happens when they’re still miserable, empty, and without direction?

Daniel Pink, author of Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, says, “When the product motive becomes unmoored from the purpose motive, bad things happen” (via). The purpose of education, as is written and expressed today, has become unmoored from the deeper more existential purpose: to discover our gifts and talents, to hone them, and then figure out ways to give them away. To serve others.

And for that, I am responsible.

My friend Glen Walenda once theorized on one of my recent blog posts, that Teachers and coaches (perhaps even parents) “often treat {children} as future people instead of people. We are so blinded by their potential we don't see them in the present.” In doing so, we concentrate on the superficial, the tangible, and the quantifiable measurements that will help them succeed (whatever that means) later on in life, when they’re future people.

Because that’s how we know we are doing a “good job,” when our students are scoring well and paying attention in class. It’s also how we’re failing.

The best comedy, according to George Carlin, is a process of digging through the layers of humanity. Instead of simple jokes, the best comedians spend their time talking about feelings and who we are, our loves and likes, our fears and nightmares, and the stuff that makes us, us. That makes them, them. The human being stuff. The stuff that no standardized test or classroom assessment can ever measure.

Curriculum, teaching strategies, and assessments are important and necessary to gauge learning, but how to live life, how to work through struggles and celebrate victories, how to engage humanity and find our purpose in life, these are what we stay alive for. These are why we learn. But because we cannot measure them, no funding is attached to them, and because it is easier to grade knowledge rather than character, education focuses on GPAs rather than character, compliance rather than curiosity; it focuses on the future people rather than the now people.

For that, I am responsible.

The most “influential and inspiring people,” according to John Dickson, “are often marked by humility” which is “the noble choice to forgo your status, deploy your resources or use your influence for the good of others before yourself” (pg 24). Fred Rogers would agree. “The real issue in life,” he believed, “is not how many blessings we have, but what we do with our blessings. Some people have many blessings and hoard them. Some have few and give everything away” (via).

Schools, however, don’t often teach students to give their resources and blessings away. Instead, we focus on individualized learning, valedictorians, and high GPA’s. We focus on counting our blessings and building resumes.

We buy letterman jackets, award honor rolls, and crown kings and queens.

People of character, however, focus on how they can best give away their gifts and resources rather than hoarding them. They care more about their classmates, their community, and whoever else might be in need. They rarely focus on their own.

They care more about living in harmony than they do standing in the spotlight.

“Harmony,” the poet, theologian, and philosopher John O’Donohue states, is everything uniquely itself, “and by being uniquely itself, part of a greater community” (via). Sadly, I have not taught that enough in my classes.

I have focused on the uniqueness of the individual, but not on how their uniqueness fits into the great narrative. I have focused on their gifts, their talents, and dreams they want fulfilled, but I have not taught them well enough the responsibility of those gifts, and the joys of giving them to others. I have focused too much time on developing their resume virtues, not their eulogy virtues.

I didn’t pull the trigger on any mass shootings, but that doesn’t mean I don’t play a part or that I’m unable to prevent the next one. Because I’m an educator, I’m responsible for building and guiding a culture. And so far, I haven’t done the best of job.

For that, I am responsible.

Andy Dufresne crawled through “five hundred yards of shit smelling foulness, {we} can’t even imagine.” Dave Cullen did the same. For ten years. Then, like Andy, he emerged, clean and redeemed on the other side.

Like Andy and Cullen, we didn’t pull the trigger. But we have pushed each other away for the sake of ourselves. And that’s why we die.

If we, as a country, truly do believe enough is enough, that “No one should ever have to go through this. Period”, and that, names of victims on the back of shirts just isn’t enough, then we too must be willing to endure the worst we can imagine and take whatever responsibility we can upon ourselves and change. We must choose another rather than ourselves, our freedoms, and our rights.

If we can do that. Then, maybe, just maybe we too can emerge from this shit-smelling foulness that isn’t hard to imagine. And when we do, like Andy and Cullen, we too can be free, and clean on the other side.

We can find redemption.

For more on . . .

A few years ago, my wife and oldest son left me and my two youngest at the time home for 265 hours. I had a stable job, was on vacation from school, and help from various friends. My wife was coming home soon.

When she finally did make it back, I was sitting on the balcony of our 7th floor apartment, trying to process the time. Here’s a piece of what I wrote:

If you know {a single parent}, show ‘em some love. Make them dinner, wash their dishes, or babysit their kids. At the very least, by their coffee because I promise, they drink more than you. A beer wouldn’t hurt either:)

If you are one, you’re my hero. (via).

This film has all the same feels. Only worse.

This film is terrifyingly brilliant. I literally feel the heat, the fear, and the panic in the little car, and I cannot help but ache for everyone involved.

The mother loves her kids, no doubt. But she’s stuck. No babysitter, no grace from work, and three little kids who need their mother to work, pay the bills, and rush them to the bathroom.

The spectators want to care for the kids. Because they’re good and decent people. Yet, they don’t see the whole and perfect picture.

The child loves her mother.

And everything is absolutely not okay.

Ugh.

How many situations like the above could be avoided if we all acknowledged the single parents around us and gave them an extra helping hand? How many children would be saved in the process?

If you know a single parent, show them some love. Make them dinner, wash their dishes, or babysit their kids. At the very least, by their coffee because I promise, they drink more than you. A beer wouldn’t hurt either:)

If you are one, you’re my hero. Sincerely.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Short Films : On Parenting : Single Parents

The film Caroline is produced by ELO films, a “co-writer / director duo Celine Held & Logan George. Their work as a team has premiered in competition at Cannes Film Festival, Telluride Film Festival, and at South by Southwest. They were named one of Filmmaker Magazine’s ’25 New Faces of Independent Film’ of 2017” (via).

You can see more of their work here.

This is pretty mesmerizing.

And if you play it with The Plague Soundtrack in the background, it gets even better.

The yellow dots are aircraft.

It is a 24 hour observation of all of the large aircraft flights in the world, condensed down to about 2 minutes. You can tell it was summer time in the north by the sun's footprint over the planet. You could see that it didn't quite set in the extreme north and it didn't quite rise in the extreme south.

Notice that as evening approaches, the traffic is predominantly from the US to Europe and when daylight comes, the traffic switches and it is predominantly from Europe to the US (via).

I’ve watched for a little while, to see if a yellow dot suddenly disappeared, but never did see one.

First, press play.

Mr. Keating has inspired teachers for generations, and probably always will. Whether it be his embodiment of Carpe Diem, standing on his desk to help his students "see things from a different point of view," or having his students march in court yards to stress the dangers of conformity, Mr. Keating was a master at inspiring minds and challenging the status quo. His boys learned to “think for {themselves} again, to suck the marrow out of life, and to express their own unique voice. Mr. Keating was a powerful leader, and one worth emulating. However, he is also the quintessential example of just how dangerous our words and ideas can be.

The opening scenes of Dead Poets Society are crucial to understanding the purpose and the pitfall of Mr. Keating. We are introduced to Welton Academy, one of the best preparatory schools in the United States, by witnessing the first day of school: the light of knowledge, Weltons’ four pillars (Tradition, Honor, Discipline, and Excellence), and the sense of overbearing and high-achieving parents. Especially for two of the main characters and roommates, Todd Anderson and Neil Perry.

Todd is following in the footsteps of his older brother, the valedictorian and merit scholar, while Neil, an only child, is trying to live up to his parent’s expectations of becoming a doctor. Throughout the movie, these two boys wrestle with their relationships with their parents, Todd dealing with his parent’s absence (sending him the same desk set for the second year in a row), and Neil with his father’s overbearing presence (forcing Todd to quit the school annual because he has “decided {Neil} is taking too many extracurriculars”). They are the same different of one another.

Then comes Keating.

Mr. Keating also “survived Welton” and is therefore all too familiar with the difficulties and dangers of its restraints. So instead of adapting to its continued and current culture, he challenges Welton, its traditions, and its purpose, and the boys suck it up completely. For them, a starving group of young boys who are eager to live life independently and to the fullest, Mr. Keating’s words and ideas are the marrow of life. Which is often the hope and desire of every aspiring leader.

Mr. Keating knows his audience. He knows their culture, what they need, and where he wants them to go. In this, Mr. Keating is a good leader. But he also has the personality and ability to get his eager yet often shy followers to go where he needs them to go. He encourages the boys to bring back the Dead Poets Society, inspires Knox Overstreet to woo and win over Chris Noel, and, in one of the most iconic scenes from the move, he breaks Todd Anderson from his restrictive shell. Mr. Keating does this because he, after weeks and weeks of teaching and investing, has earned the boys’ trust as a friend, as an educator, and as a philosopher. In this, Mr. Keating is a great leader, and so his influence and impact continue to grow.

At the beginning, in one of his first classes, Mr. Keating has his boys rip out the introduction of their textbook, Understanding Poetry. “Be gone Mr. J. Evan Pritchard!” he yells, encouraging them to break through the bonds that bind their minds and actions, “I want nothing left of it.” Then, as he retreats to his office to grab a trash bin, the Latin teacher, Mr. McCallister, happens to walk by, misinterpret the chaos, and barges in. When Mr. Keating returns, they engage briefly, then depart. Later, at lunch, they discuss the minds of young men and the purpose of education. Shortly after, and throughout the movie, the two become friends, talking over tea and engaging in slight moments of friendship. Near the end, Mr. McCallister is seen waving goodbye from the window, an indication that he will miss his friend and, although not always in agreement, has grown to respect Mr. Keating and his views. A mark of any good leader.

Mr. Keating also shows the breadth and depth of his influence over the boys when he rebukes Charlie Dalton for his “lame stunt” he pulled with the telephone call that had God calling, asking Welton to allow girls into the school. “I thought you’d like that,” Charlie argues, confused at Keating’s rebuke, “"There's a time for daring and there's a time for caution, and a wise man understands which is called for." Charlie not only hears these words, he understands and applies them. As Mr. Keating leaves, Charlie puts away his drum and stops telling his story, because he knows it no longer matters. Living life of passion does not mean “chocking on the bone.” In this, Mr. Keating, yet again, demonstrates his leadership in that he not only inspires, he corrects and directs. He isn’t afraid to rebuke his boys, and instead of hammering them for their mistakes, he uses their mistakes for teachable moments, which only builds and strengths the bond of trust between him and them.

Then, at the height of his teaching, when the boys seem to be soaring, when Neil is staring in the play, when Knox has finally won over his girl, and after Todd has inspired every English teacher and want-to-be-poet with his sudden recital of “The Sweaty-toothed Madman,” all hell breaks loose. Neil is suddenly whisked away by his father who spits at Keating, “You stay away from my son.” Soon after, Todd is shaken awake in the middle of the night and told through soft whispers, “Neil’s dead”, and Mr. Keating is to blame.

“You guys didn’t really think he could avoid responsibility, did you?” Cameron says to the boys while they hide in the attic storage.”

“Mr. Keating responsible for Neil, is that what they’re saying?” Charlie asks.

“Who else do you think, dumbass?” Cameron shouts, “Mr. Keating put us up to all this crap, didn’t he?” And Todd won’t stand it.

“That is not true, Cameron, and you know that,” he says, holding back tears, “He didn’t put us up to anything, Neil loved acting!”

“Believe what you want,” Cameron shoots back, “But I say, let Keating fry.”

This scene is crucial, for two reasons. One, the choice of characters and the words they use are extremely critical. Cameron has always been portrayed as the one not fully immersed in the teachings and ideas of Keating, so it isn’t a surprise that he sides with the administration. It also is not surprising that he does so with such cruelty, because there needs to be a quick and clean separation. “Let Keating fry,” is heartless and calculated, but it also creates in us, the viewers, a sense of “Us vs Them”, and there’s no way we are them – those who blame Keating for Neil’s death. We are part of the Dead Poets, those who believe in Keating, his teachings, and Carpe Diem, and we believe he is innocent!

Great leaders, however, do not have the luxury of passing responsibility. Great leaders, at all times, must evaluate the actions and reactions of those they care for and ask, “What role did I play? Where am I responsible?” For Keating, he needs to look no further than his classroom.

In the most watched and adored scene of the movie, Mr. Keating brings Todd Anderson up to the front of the classroom and helps him create poetry, and it’s magical.

Todd is terrified, believing “everything inside of him is worthless, and embarrassing,” and therefore refuses to write a poem or speak in front of the class. But Mr. Keating, being the great leader that he is, refuses to let him sit comfortably in his shell. “I think you’re wrong,” he argues, “I think there is something inside of you that is worth a great deal.” Shortly after, he pulls Todd to the front of the class and asks him look at Walt Whitman and describe what you see, "Don't think, answer, go!" Mr. Keating says, "free up your mind, use your imagination, say whatever comes to mind, even if it's total gibberish." And out comes one of the most quoted poems about Walt Whitman ever uttered.

However, what Mr. Keating fails to supply is context and an anchor for such behavior because, applying that same technique, that same way of thinking and living to other emotions in a very different scenario results in the death of Neil Perry.

In the final scene of the movie, right before the students climb on their desks, the headmaster is teaching the class. He asks what they've been reading, and Cameron responds with, "Mostly the Romantics."

"What about the Realists?" the headmaster asks?

"We skipped over that part," Cameron responds.

Mr. Keating knows his boys need a break from tradition, that they need to be free thinkers, but what he fails to understand is that he was a graduate of Welton Academy where he was encouraged/required to wrestle with and learn from a variety of minds and ideas, not just the romantics. Mr. Keating had a well-rounded perspective of life and living. However, with his boys, he provided very little balance. He didn’t have them think for themselves, evaluating which philosophies of life were more appropriate, and why. Instead, he only focused on the Romantics, and this, for young and influential minds who are used to strict structure, oppression and tradition, was extremely careless.

Mr. Keating didn’t kill Neil Perry. Nor is he solely responsible for Neil’s death. He did, however, fail to grasp his influence upon his boys and properly assess their needs and struggles. The boys needed a break from tradition and the ability to think for themselves, just as Mr. Keating believed, but they also needed structure and balance to their rapidly changing hormones and emotions. They needed the freedom to feel and express their emotions, but they also needed to know how to evaluate them, to balance them, and to check them against other, much less ambiguous and fluctuating truths such as principles and ethics. They needed to be taught how to evaluate their emotions, not just embrace them.

In many respects, Mr. Keating was a great leader. He inspired his boys and, for the most part, brought out the best in them. However, he was incomplete. “Don’t think, just answer,” he taught them. But outside confines and safety of his classroom, this way of thinking lead to death.

Mr. Keating doesn’t deserve to fry, as Cameron suggests, but he does deserve a healthy dose of responsibility for the role he played. “In my class, you will learn to savor words and language,” Mr. Keating encourages his boys, “No matter what anybody tells you, words and ideas can change the world.” However, placed in the minds of young men who are unable to grasp their severity and consequence, who cannot align and judge them to strict and grounded principles and ethical standards, those words and ideas can also destroy.

And for that, Mr. Keating is responsible.

Image from LaunchGood.com

Chimamanda Adichie said it best, “The problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete.”

“The consequence of the single story is this” Adichie continues, {{i}t robs people of dignity. It makes our recognition of our equal humanity difficult. It emphasizes how we are different rather than how we are similar.”

Muslims Unite for Pittsburgh Synagogue was set up to help “support the shooting victims with short-term needs (Funeral Expenses, Medical Bills, Etc)” and, to date, it has raised over $230,000 “to help victims and their families following the shooting massacre at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh on Saturday.”

To create a single story, “show a people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become.” Even when that is not exactly who they are.

For more on . . .

This, from a friend: “I've been enjoying this song for the last year or so, but came across the video for the first time last night. I cried as I watched it with my kids. Thought you might enjoy.”

Long hair and longer stride

Skateboard fair with a primal tribe

And your cut off painter pants

Chargin' down the craggy mountains with our thrift store friends

And who you find so

So in love with the falling earth

Oh you wake in the middle of the falling night

With the summer playing coy

In the attics of the city night

We talked corso and the MC5

And you could dance live

We were all alright

And only the wild ones

Give you something and never want it back

Oh the riot and the rush of the warm night air

Only the wild ones

Are the ones you can never catch

Stars are up now no place to go, but everywhere

One I met in the green mountain state

I dropped out, and he moved away

Heard he got some land down south

Changed his name to a name the birds could pronounce

And only the wild ones

Give you something and never want it back

Oh the riot and the rush of the warm night air

Only the wild ones

Are the ones you can never catch

Stars are up now no place to go but everywhere

(No place to go but everywhere)

And in the city the mayor said

Those who dance are all mislead

So you packed your things and moved to the other coast

Said you gonna be like Charlie Rose

And only the wild ones

Give you something and never want it back

Oh the riot and the rush of the warm night air

Only the wild ones

Are the ones you can never catch

Stars are up now no place to go, but everywhere

Only the wild ones, give you something and never want it back

Oh the riot and rush of the warm night air

Only the wild ones

Are the ones you can never catch

Stars are up now no place to go, but anywhere

Hmm, hmm hmm

Hmm, hmm hmm

Hmm, hmm hmm

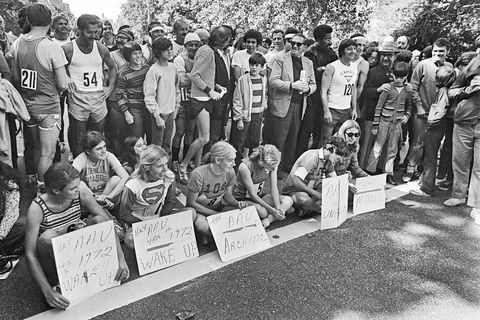

Before the 1970s, women were not welcome at the world's great marathons, but a few brave pioneers sought to challenge that system. Six Who Sat tells the story of two iconic moments in women's running, both captured in photographs. The first, from 1968, is of a race director trying to physically restrain a woman from running the Boston Marathon. The second, from 1972, is of a protest at the New York City Marathon that forever changed women's ability to participate in the sport they loved.

While listening to this podcast, Six Who Sat, by the 30 for 30 ESPN podcast, I couldn’t help but think about golfing. I hardly ever golf, but when I do I always notice the different tee boxes: Competition tees (white), men's tees (yellow), women's tees (red) and sometimes blue tees for veterans and juniors. Why hasn’t anyone “sat” for this obvious display of gender bias? Of course the woman’s tee is closer, they can’t hit nearly as far!!!

For more on . . .

Banksy also sold one of his most iconic images for 1.4 million. Then, as a prank, the frame shredded the painting. Pretty brilliant, but also, kind of a jerk move.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Art : Documentaries : Banksy

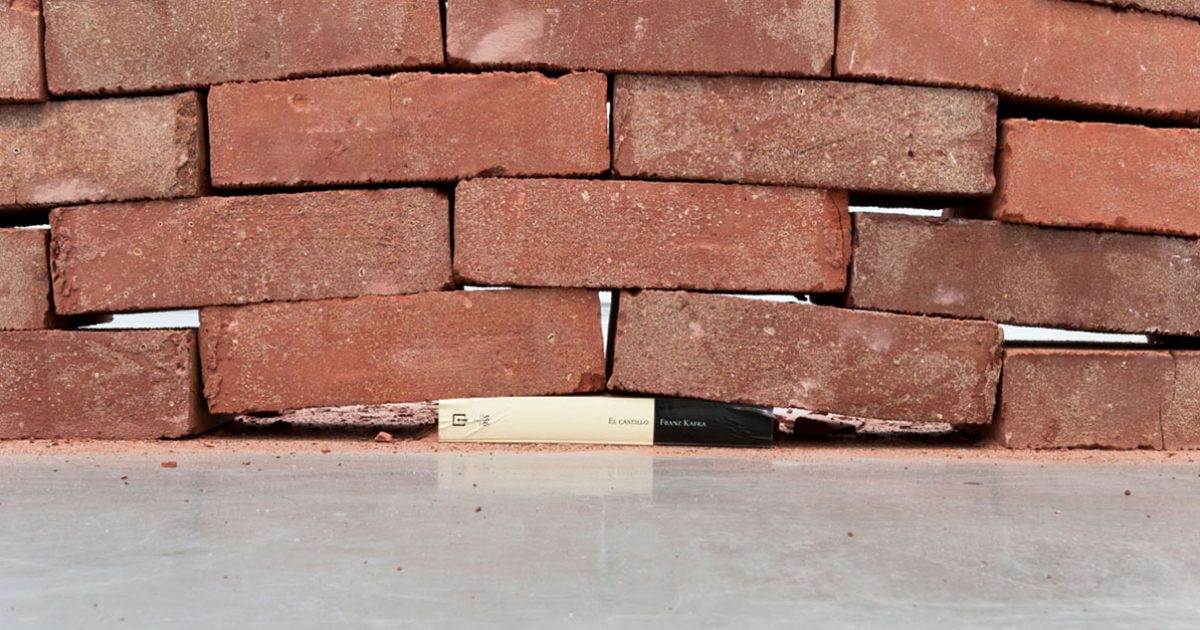

In his work, literature becomes a tool that articulates situations, places and objects where each piece is full of theoretical meanings related to one another.

“Jorge Méndez Blake is a Mexican born artist that draws connections between literature and the visual arts through assemblage, drawing, and environmental interventions” (via).

He is also a man who would rather quote another than create something new, which I find truly intriguing.

“If making my detox public is gonna help somebody, even, literally, just one person, I’m all for it.”

With so much detachment and insincere living, I feel like these types of videos and “putting myself out there” moments will become more and more the norm. Which means the pendulum will be swinging into radical realism.

For more on . . .

“Maybe not everything is supposed to be comfortable?”

Heavyweight “is the show about journeying back to the moment when everything went wrong,” and then trying to pick up the pieces, make amends, or seek forgiveness. It’s a brilliant show. I’ve listed some of my favorite episodes here, or you can listen to all of them on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

For more on . . .

Image by @storyanthology

“Almost nothing was known about how children even explored the world,” Roger Hart explains in interview with Alix Spiegel, “and then I came across a book on baboons. And I realized that we knew more about baboons' everyday behavior than we did about children's behavior outside of school.”

So, in the 1970’s, Roger Hart set out to learn more about children’s behavior by filming them in their natural habitats and away from their parents. “There were 86 children between 3 and 12 years of age,” Hart explains, “and I worked with all of them, all of the waking hours for two and a half years, I was with them. They were my life, these kids,” and they took him everywhere.

He mapped their exploration, adding descriptions such as, “frequent paths, not used by adults.”

“They had more than the run of the town,” he explained, “Some of them would go to the lake, which would be on the edge of town, and the lake, you'd think, would be a place that would be out of bounds” because the parents weren’t motivated by fear. There was no talk of abductions, stranger danger, nothing. So the kids wondered and played all over town.

Not so today.

“{S}everal years ago, Roger went back to the exact same town to document the children of the children that he had originally tracked in the '70s, and when he asked the new generation of kids to show him where they played alone, what he found floored him . . . The huge circle of freedom on the maps had grown tiny.”

Even though the town was exactly the same physically and demographically, even though “the town is not more dangerous than it was before” and that there is “literally no more crime today than there was 40 years ago” parents are operating according to fear, and kids are staying closer to home.

The modern life, according to Ralph Adolphs, a professor at Caltech who spent decades studying fear in the human brain “is constantly triggering our fear in all kinds of ways that our natural world didn't.”

News reports that depict violent scenes and soundbites of murders, of men and women describing atrocious moments of violence and fear, and the many other images and ideas of horror throughout the world constantly surrounds us. “And Adolphs argues that because of our wiring, we are just not set up to ignore it,” which distorts our experience of the world and activates “our fear when we don't need it.”

We’ve become overly fearful and extremely protective, even as adults, with our maps of exploration growing smaller and smaller. Geographically, and intellectually.

“Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness,” Mark Twain writes, “and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.”

Luckily, the youngest of us have not learned to be fearful or bigoted yet. May we all learn a lesson from these young explorers and their adventurous spirit.

Kids do not want to be contained.

They are built for adventure.

I’m trying to be the voice or the image of the people who don’t have that voice . . .

When you walk into a class and see me, I want you to feel taken care of . . .

That’s why I became a yoga teacher, because I wanted to share that with other people . . .

I see your white, I see your black, I see your fat, I see your skinny. I don’t care what you look like, I just want you to come in and open your mind and open your heart.

For more on . . .

I’m in Missoula this weekend, attending a principal’s conference, enjoying the mountains, and writing papers. Yeah, it’s pretty awesome.

I’ve written various chapters for a possible book on education but have been struggling with how to tie them all together, “What’s the overall purpose?” I keep asking.

At a recent teacher’s conference, I asked those in my workshop, “Why do kids need an education? Why do they have to go to college?” then they discussed. Their answers weren’t shocking.

But then I asked, “Why does a student need your subject? And why do they need you as their teacher?” They had a more difficult time answering this question.

Later the following night, while watching the sun set behind the Missoula mountains, an to my question, “What is the purpose of my book” surfaced, “To discuss why we teach.” So often, at conference or in literature, we as educators discuss What to teach and How best to teach it, but how often do we consider Why we teach?

I asked the group that question too, “Why do we spend so much time on the What and How and not on the Why?” For an almost awkward long while, they were quiet. Then, a middle-aged lady leaned over and whispered to her friend.

“What was that?” I asked, “Can you say that again?”

“Because it’s easier,” she said.

“Exactly,” I said.

This weekend’s writing is based almost entirely off the book, Humilitas: The Lost Key to Life, Love, and Leadership. It’s a simple read, but it is also one of the most profound because it hits to the core of why we teach, lead, and live.

Summary:

The thesis of Humilitas: A Lost Key to Life, Love, and Leadership is that most “influential and inspiring people are often marked by humility” (pg 19). But this wasn’t always so. For many years, men and women would never have considered humility a lost key to life, an honorable character trait, or something worth emulating. It wasn’t until just a few thousand years ago that humility was introduced into the Western world, forever changing the way we think, and the way we lead.

According to John Dickson, a historian and senior research fellow of the Department of Ancient History at Macquarie University, the ancient Greek and Roman world was built up on an honor/shame culture. In this time, a father would not have been concerned with whether his son was happy (in the modern sense) “or made money or lived morally, but whether the boy would bring honor to the family, especially to his father, and to himself” (pg 86). Honor could come through participating in a military victory, advancing through the ranks of official society, or by inventing/creating something that would greatly benefit the village – where his name and his family’ name could be pointed to and remembered. “In all of these things,” Dickson writes, “the thought was not so much the importance of conquering evildoers, making a difference to civic life or benefiting others; the chief good was the respect and praise that comes through these activities and the way they confirm the merit of the one so honored” (pg 86). Life was about being honored, remembered, and revered. Humility was rarely, if ever, considered virtuous because it was for the lowly, not the honorable.

Humility towards the gods was appropriate because the gods could kill you. Humility was advisable to emperors too, because they too could kill you. Humility towards an equal or lesser was completely out of the question because “merit demanded honor, thus honor was proof of the merit (pg. 87)”.

It was in this context that ancient Greeks and Romans thought nothing of praising themselves in public or, better still, getting others to praise them because it was proof of their merit.

Then, from seemingly nowhere, came the teacher from Nazareth.

“Unfortunately, after two thousand years of Christian history,” Dickson writes, “it is difficult for people in the modern West to think of Jesus of Nazareth in a non-theological way” (pg 101). Historians however, have very little difficulty in laying “out the sources of his life, describ{ing} the methods historians use for testing claims about him, plac{ing} him in the context of Roman and Jewish history and outlin{ing} what most scholars agree are the facts about Jesus’ life, teaching, execution, and immediate impact” (pg 102). And according to historian scholars, Jesus’ immediate impact upon the Western world was introducing humility as a virtue. Because of Jesus, humility is no longer scoffed at or looked down upon, it is a badge of honor and pride and the mark of any great leader.

Humility is “the noble choice to forgo your status, deploy your resources or use your influence for the good of others before yourself”, it is the “willingness to hold power in service of others” (pg 24). It is therefore impossible to be humble, in the real sense of the word, without a healthy understanding of one’s own worth and abilities (pg 25). Great leaders are not humble because they are sheepish, think lowly of themselves, or because they are “down to earth.” They are humble because when they look in the mirror, what they see is their gifts and talents and resources. They know fully well how good they are, strong they are, or powerful they are. And they must. In order to be humble they must be fully aware of what they have/are, so they can be equally aware on how best to give it away.

“Humility,” Dickson writes, “is more about how I treat others than how I think I think about myself” (pg 25). Although they have a healthy perspective of themselves, it is not their focus.

Men and women who understand this concept and embrace it as a principle virtue, they become the most influential and inspiring people in our schools, companies, communities, and world. By living and leading through humility, they not only gain the trust and admiration of those they lead, they inspire and encourage everyone around them to live to their fullest and greatest potential, fully embracing their gifts and talents yet deploying them for the good of the community, not just themselves.

Analysis:

Several years ago, when I first married and was still considering my possible profession, a friend offered me a leadership book, “How to Make Your First Million, By the Age of Thirty,” or something like that. I believe that individual meant well by the gift because I truly do believe that individual wants to help make the world a better place. Sadly, that cannot be said about many leaders in any work force, which is why, sometimes, the greatest leaders refuse to take on leadership responsibilities. Because the stigma of those in leadership is often selfishness and materialism. They become leaders so they can make millions, have more benefits, or gain more power; it’s about them, not others.

Leaders such as these care deeply about What they do and How they do it because they compliance from their staff; their concern is efficiency, productivity, and numbers.

“If we're going to say, I'm not a success unless I'm on that best-seller list or this best-seller list, or I get that thing in advance or I have these sorts of ratings,” Seth Godin states, then “you are playing the game of the industrialist,” and therefore missing the point. “The point is,” he concludes, “will someone come up to {you}and say, based on what I learned from you I taught 10 other people to do this, and we made something that mattered” (Godin, 2018).

The point of leadership is the same, to help others become the best version of themselves so they can, in turn, help 10 other people do the same.

If, as a leader, the purpose is to be liked, popular, or successful (according to numbers, money, or achievements), then their foundation – their Why – becomes subject to personal gains and losses, not the community’s best interest. And when their personal purpose motive becomes unmoored from the people motive, bad things, scary things, and destructive things begin to happen. They begin to deploy their resources or use their influence for the good of themselves rather than for the benefit of others. They begin to abuse their authority.

According to Dickson, a principal, CEO, and president, have structural power that has been handed to them by an organization. They have “the power to hire and fire, set directions, approve budgets and overrule colleagues where there is disagreement” (pg 39). Leaders who wield this power selfishly, who’s aim is to serve and bring honor to themselves and their position, do so because relying on their authority is proof of their status and authority, which in turn creates a culture of fear, mistrust, and survival.

In contrast, if a leader’s purpose is to help, to honor those they lead, and to employ their resources for the betterment of the community, if a leader sees their position of power not as a right but as a privilege and responsibility to serve rather than be served, they will create a thriving culture of curiosity, trust, and innovation.

This is why John Dickson’s book is so crucial, because it addresses the Why of leadership and emboldens good leaders to be great leaders. It allows leaders to fully acknowledge who they are and the gifts they’ve been given, to pursue and strengthen those gifts, and to step into positions where those gifts and talents are most needed. Dickson’s redefining of humility gives talented, gifted, yet selfless individuals the push they need to step into spotlight roles because they know, by stepping into a leadership position, their focus will not be themselves, but those they serve.

Just like Jesus.

John Dickson, like many non-Christian historians, believed Jesus of Nazareth to be the defining example of humility. And whether or not one believes him to be the savior of the world or not, his example (in relation to humility) is one worth emulating.

The Apostle Paul wrote to the church at Philippi:

Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit. Rather, in humility value others above yourselves, not looking to your own interests but each of you to the interests of the others. In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus: Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man he humbled himself by becoming obedient to death— even death on a cross!

Christ did not consider his authority as God’s son as something to be used for his own advantage, it was something He needed to give away! His power, his ability to provide eternal life, his authority over death meant He had something nobody else did, and He understood this. He had to in order to properly and fully serve the world. Christ embraced his Godship, his authority, and chose to humble Himself by becoming obedient to death (allowing Himself to die) so that others may live. He didn’t use His kingship to be honored and served (to make millions), but to serve. That is the true definition of leadership.

It is also the perfect recipe for creating a culture of trust.

Plato once believed, “that all of us tend to believe in views of people we already trust . . . even a brilliantly argued case from someone we dislike or whose motives we think dubious will fail to carry the same force as the case put forward by someone we regard as transparently good and trustworthy” (pg 42). Leaders who assume leadership positions with a faulty and selfish Why are not trustworthy. They are the exact opposite, which is why they resort to tricks and gimmicks. In contrast, leaders who spend their time and energy thinking about and serving, who care more about the wellbeing of others than themselves are easily trusted. “Leadership is not about popularity,” Dickson writes, “It is about gaining people’s trust and moving them forward” (pg 43). It’s about their advancement, not our own.

Another outcome of a life lived in humility is that one will “learn, grow, and thrive in a way the proud have no hope of doing” because “people who imagine that they know most of what is important to know are hermetically sealed from learning new things and receiving constructive criticism” (pg 116). This is a radically important concept for a leader. If a leader is not living with true humility, they are unable to learn and grow because in order to do so, they must admit – either privately or publicly – that their skills and gifts and talents are insufficient. And if they’re insufficient, the spotlight will move and shine upon someone else, which could be devastating. However, if a leader is marked by humility, they and their spotlight are already focused elsewhere, leaving them free and open to new thoughts and new ideas, allowing them to grow and learn and better serve those they are leading. “In his battle against early twentieth-century rationalism and self-reliance,” Dickson writes, “G. K. Chesterton argued that human pride is in fact the engine of mediocrity. It fools us into believing that we have ‘arrived’, that we are complete, and that there is little else to learn” (pg 120). Such is the trademark of a selfish leader.

Being a leader marked by humility does not mean, however, that he or she is soft, easily tossed around, or meek and mild. Nor does it mean being loud and pushy. “One of the failings of contemporary Western culture is to confuse conviction with arrogance,” Dickson argues, “the solution to ideological discord is not ‘tolerance’,” he writes, “but an ability to profoundly disagree with others and deeply honor them at the same time” (pg 23). Having strong opinions and deeply held convictions is not a hindrance to humility. In fact, in many cases, it is the mark of it. As long as we are willing and able to use or withhold those convictions for the good of others before ourselves.

Closing:

Living a life and leading with humility not only signals security, it fosters a healthy sense of self-worth that is rooted in service rather than achievement, in giving and not taking. The more leaders rely on achievement or popularity for a sense of worth, the more crushing every small failure or simple criticism will seem.

In contrast, knowing, living, and leading with a purpose beyond myself that is rooted in the principle of humility provides an impenetrable fortress of security and freedom, for leaders as well as for their staff. If a staff understands that their leaders decisions and purpose is to serve and honor them, if they believe that their leader’s hope is for them to succeed, to reach their utmost potential, and to be the very best version of themselves, a community that supports and trusts one another, that grows and learns from another other, and that defends and protects one another will be established. A type of culture where everyone is embracing their gifts and talents and using them for the benefit of the community, not just themselves, because they know and trust their neighbors are doing the same. “When people trust us, they tend to believe what we say, and few are considered more trustworthy than those who choose to use their power for the good of others above themselves” (pg 147).

A leader marked by humility is also not afraid to admit mistakes because they are not concerned about their perfect shine. They’re fully aware of their faults, and the faults of others, and therefore choose to freely admit their flaws and mistakes because they know it is what’s best for the progress and strength of those they lead. “Mistakes of execution are rarely as damaging to an organization, whether corporate, ecclesiastical or academic, as a refusal to concede mistakes,” Dickson states. If a leader is unwilling to admit his or her mistakes, if they are insecure and unable to fail in front of those they lead, they can never expect their school or community to try new things, make amends for mistakes made, or seek reconciliation from those they’ve offended. The culture will be stale and shallow, with each person operating out of safety and survival rather than curiosity and trust. “Apologize to those affected,” Dickson argues, “and redress the issue with generosity and haste” (pg 130).

Leaders want their staff to believe that they are not only competent in their job, they also want their staff to be proud of them as their boss, to brag about them, and to consider them a superstar, like players do who have been coached by some of the greats. “I played under Coach K,” or, “I was one of Coach Ditka's players.” Athletes who talk this way are proud of their journey and the coach that inspired them, because those great coaches understood humility.

Dickson writes, an "inspiring leader must control his ego and throw his energies into maximizing other people’s potential.” But also, they must ensure that “{the players} get the credit” (pg 156). Coaches who brag about their play calling, their clock management, or whatever instantly lose the respect of their players. Great coaches brag about their players, lift them up and celebrate them; they shift the spotlight, fully and completely, on others and their accomplishments, not their own.

The most influential and inspiring people are often marked by humility. They willingly forgo their status, deploy their resources, or use their influence for the good of others before themselves. They consider others as more important than themselves, and in so doing, they change the world.

For more on . . .

Here are three videos by The Nerdwriter, “a weekly video essay series that puts ideas to work.”

I’ve always enjoyed art and wish I could participate, but I’ve also always felt bit distant. Even though I look and stare and draw conclusions, it often seems the art “Won’t give an inch.”

“Boredom is exactly when we feel time and being most acutely. It can inspire a profound mood.”

Also check out Movies inspired by Art, see how The Village stole from The Princess Bride, or more ideas from Nerdwriter1.

For more on . . .

-N- Stuff : Art : Nerdwriter1