The best fiction writers write like they’re in love—and edit like they’re in charge.

First drafting should be a wild and wonderful ride, full of discovery, dreams and promises. But at some point you have to settle down and make the book really work. You need to approach your manuscript with sober objectivity and knowledge of the craft.

Having reviewed hundreds of manuscripts over the years, I’ve identified the five mistakes that most regularly turn up. Start your revision by addressing these, and you’ll immediately change your story for the better.

This is the introduction from a Writer's Digest post entitled, The 5 Biggest Fiction Writing Mistakes (& How to Fix Them). In it, James Scott Bell does exactly what the title suggests, he identifies the 5 biggest fiction writing mistakes and shows how to fix them.

But what if these truths were applied to life? Truths such as:

1. Happy People in Happy Land

Chief among the most common problems, in first chapters especially, are scenes presenting characters who are perfectly happy in their ordinary worlds. The writer thinks that by showing nice people doing nice things, readers will care about these pleasant folk when the characters are finally hit with a problem.

But readers actually engage with plot via trouble, threat, change or challenge. . .

Yet, most of the time what we say we desire most is to live a happy life in a happy land. Yet, when it comes to stories, happy people living in happy lands bore us . . . because it just isn't all that relatable. Like a good story, there needs to be adventure.

2. A World Without Fear

The best novels, the ones that stay with you all the way to the end—and beyond—have the threat of death hanging over every scene.

Death comes in three forms. Physical death is a staple of the thriller, of course. But there’s also professional death, where the main character is engaged in a vocation and the particular matter at hand threatens that position: A cop assigned a case that may mean the end of his career. A married politician falling for a young staffer. A devoted mother losing the child she loves to drugs. Your job, if it’s vocational death overhanging your novel, is to make whatever problem the protagonist is facing feel so important that failing to overcome it will mean a permanent setback to his main role in life.

There’s also psychological death (“dying on the inside”), most often emphasized in character-driven fiction. This is where the romance genre comes in. It has to seem as if the lovers must end up together or their lives will forever be less than what they could have been.

Regardless of which form you use, you must put death on the line so fear may be felt throughout. Fear is a continuum—it can be simple worry or outright terror. You can put it everywhere. And you should.

Once the story is underway, scenes where fear isn’t present in some form mean the stakes are not high enough or the characters aren’t acting the way they should in the face of death.

Achilles says the same:

3. Marshmallow Dialogue

Dialogue is the fastest way to improve a manuscript—or to sink it. When agents, editors or readers see crisp, tension-filled dialogue, they gain confidence in the writer’s ability. But dialogue that is sodden and undistinguished (marshmallow dialogue) has the opposite effect.

Pro dialogue is compressed. Marshmallow dialogue is puffy.

Pro dialogue has conflict. Marshmallow dialogue is overly sweet.

Pro dialogue sounds different for each character. Marshmallow dialogue blends together.

Fortunately, the fixes are simple.

First, make sure you can “hear” every character in a distinct voice. . .

Second, compress your dialogue as much as possible, cutting fluffy words, whole lines or even entire exchanges. Here’s an example:

“Mary, are you angry with me?” John asked.“You’re damn straight I’m mad at you,” Mary said.“But why? You’ve got absolutely no reason to be!”“Oh but I do, I do. And you can see it in my face, can’t you?”The alternative:“You angry with me?” John asked.“Damn straight,” Mary said.“You got no reason to be!”Mary felt her hands curling into fists.

Finally, when writing dialogue be sure to include some sort of tension in every exchange. Remember fear? At the very least you can have some aspect of it (worry, anxiety, fright) going on inside one of the characters so that communication is partially impaired. Try playing up the different agendas each character has in a scene. Let them use dialogue as a weapon to get what they want.

Perfect for life, right? When speaking (in real life) speak clearly and don't fluff, be honest not sugar coated, an original (confident) not an echo, and be a great listener.

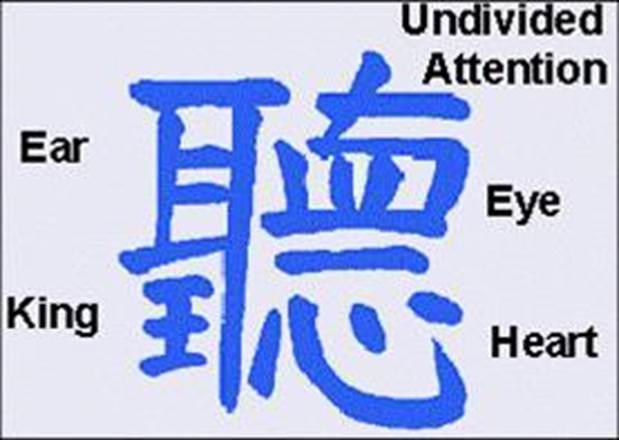

The Chinese character for "listen" is this:

When engaged in a dialogue, listen with your ears, your eyes, and heart. Treat the speaker like he or she is king. Which means although we are honest and original, we are also respectful.

Beautiful.

4. Predictability

Readers like to worry about characters in crisis. They want to tremble about what’s around the next corner (whether it’s emotional or physical). If a reader knows what’s coming, and then it does in fact come, the worry factor is blown. Your novel no longer conveys a fictive dream but a dull ride down familiar streets.

The fix is simple: Put something unexpected in every scene. Doing this one thing keeps the reader on edge. . .

Life is unpredictable. No matter how many lists we create, plans we make, or details we check and recheck, we are not in control.

Dull rides that lead us down familiar streets are safe, but boring. As Bilbo says, “It's a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don't keep your feet, there's no knowing where you might be swept off to" or what what you'll discover.

A life that is unpredictable is Life.

5. Lost Love

As I said up front, writing a book is like falling in love. Outlining and planning are the wooing. Drafting the novel is your commitment to marriage (which would make the opening scenes the honeymoon). But at some point, you and your book will likely need some marriage counseling. Because when you lose the verve for your material, it shows.

So how do you regain lost love? The surest way is by going deeper into your characters.

Start with backstory. Maybe you’ve already done an extensive bio for your main character. Try starting a new one. Keep the best of the old material, but put in plenty that’s new.

Focus on the year your character turned 16. Create an account of what happened at that crucial stage. What incident shaped her? What romances, heartaches, tragedies? Write those scenes in detail.

Do this for your antagonist, too, and your secondary characters. Soon enough you’ll be excited to get back to your story.

Also, try focusing on what your protagonist yearns for. We yearn because we feel a lack, a need, a hole in our souls. So yearning is about connection. This, in fact, is the power of mythology, some of the best storytelling of all time. Joseph Campbell taught that myths were a way of gaining connection to something transcendent, a life source, an essential mystery.

Readers, too, yearn for connection—with stories they can get lost in and be moved by. Fix these five areas in your work, and your books can be among them.

Holy Crap. Think of all that could happen to relationships if we applied THIS truth? Sheesh.

Thanks for reading, and good luck!