Sure, the acting isn't Oscar worthy, but it's engaging. It forces a new interpretation of the song, they lyrics, and the message - it asks us to see the known and memorized from a different perspective. And for that, I applaud.

Should we Say “And” Instead of “But”?

I stumbled across the following article and thought it worth storing away because I like the discussion it raises, or at least should raise. I'll ask the question at the end.

This post is from Nicole Francesca:

In Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, a “dialectic” refers to the idea of two truths being true simultaneously, even if they seem to oppose one another. It’s a practice in removing ourselves from black-and-white, either-or thinking, which is one of the greatest limiting factors in our collective ability to grow. We’re so used to seeing things as one-or-the-other and never as both-at-once that we unconsciously choose a side and live there. It needn’t be so. It’s not an easy transition always, but here’s the trick that I learned this first year in grad school to become a clinical social worker (which is a long way to say “therapist”):

Whenever you’re about to say “but,” replace it with “and,” or “and it is also true that.”

Fair warning: everyone that is very used to standing at the either-or edge of the both-and lake will not be amused by your commitment to swimming. They may have never even heard of such an outrageous idea, as I had not, of allowing both things to be true at once.

And for good reason. How can we rectify something good as also having bad elements, and vice versa? That makes the black-and-white territory quite gray indeed, and, my friends, we are fucking terrified as a people of the gray area.

It means we have to dig deeper to figure out how we feel about things, what our actual motivations are. The gray area removes the ease of simply choosing a side and leaving it at that. The other factor is this: anyone who has been on the receiving end of a “this truth, but this truth” knows that anything before the “but” is lost to oblivion forever.

I love you, but I can’t stay.

See how that works? We can’t even hear the shit before the “but,” and for good reason. “But” ends dialogue. It says, “the first truth is not nearly as important as the second truth.” Turning it into, “I love you, and I can’t stay,” opens a door for exploration, and values the first truth just as much as the second.

I encourage you to give it a try, and I’m going to give you some examples from my own life, because it took me a good while to commit to the both-and—and now I’m sold for life.

I am angry at the state of the world, and it is also true that I am in love with every small beautiful moment of each day.

I am confident, and sensitive.

Fully experiencing grief is the only way to move through it, and it is also true that grief hurts in ways that tear apart the very soul.

Being poor has made me resourceful beyond measure, and it is also true that poverty fucking sucks.

I’m the only one that can repair the damage incurred to me, without my consent, during my childhood, and it is also true that that’s really unfair.

The difference in how the statements feel when you remove the “but” has a palpable feel to me. Do they for you? It allows the reality of pain to exist without denying the reality of responsibility, or the reality of what seems to oppose the pain. It allows us some small measure of liberation without losing accountability.

The binary of either-or is a lie. As humans, we’re meant to swim in the both-and lake, and explore the deeper-than-surface shit. Joy can include grief, and pain can include beauty. It often does, without us even realizing it.

Side Note: I also want to make note that this can be used by people with nefarious intent and it’s important to be able to recognize that. Any tool for healing will be twisted as tool for control by those who need control, even if they don’t realize they desperately need it. For example:

“I hurt you, and my love for your made me do it.”

Be always sure to listen to exactly whom is taking responsibility for the gray area in which they wade.

So here is my question:

Does this mean we should never say "but"?

I love this article because it does highlight how we are "so used to seeing things as one-or-the-other and never as both-at-once that we unconsciously choose a side and live there." And I think you would agree that we see this in most everything: religion, race, personalities, etc..

So again, does this mean we should never say "but"? And if not, where? When? On what topics, issues?

Thank you Nicole for inspiring a discussion - even if it is only with myself.

Cathedral, by Raymond Carver

Ditching Empathy is a Bad Idea

Paul Bloom, psychologist and Yale professor, argues that empathy is a bad thing—that it makes the world worse. While we've been taught that putting yourself in another's shoes cultivates compassion, it actually blinds you to the long-term consequences of your actions. In this animated interview from The Atlantic, we hear Bloom’s case for why the world needs to ditch empathy.

Video by The Atlantic

- Empathy: the ability to understand and share the feelings of another.

Bloom's misuse of empathy creates a problem, namely, that he's wrong.

Empathy, deep and real empathy, isn't done for the purpose of self, "to get a buzz out of it", but for another - to understand and share in the pain they are suffering. To connect with them, for their sake. Not ours.

Perhaps the reason why we care about the baby in the well is because it's here, in front of us, and we can do something about it. The war is over there, untouchable . . . what possible difference can we make? For many of us, not much.

But we can save the child in the well.

"Selfish moralizing" is an issue worth discussing and probably one we should be against, but not empathy.

Empathy breaks down the walls of diversity, allowing us to "understand and share the feelings of another." It asks us to think not of ourselves, but of others - which is never a bad thing.

But Blooms is right, "If [we] really want to make the world better, spend less time trying to maximize [our] own altruistic joy." But then he says, "And in a more cold-blooded way think, 'how can I help other people?'"

And the answer to that Mr. Bloom is this: by being warm-blooded, and empathetic.

The Millennial Question : Simon Sinek

Diversity Makes You Brighter

By SHEEN S. LEVINE and DAVID STARKDEC. 9, 2015

AFFIRMATIVE ACTION is back before the Supreme Court today. The court has agreed to hear, for the second time, the case of Abigail Fisher, a white applicant who claims that she was rejected by the University of Texas at Austin because of her race. Ms. Fisher invokes the promise of equal protection contained in the 14th Amendment, reminding us that judging people by their ancestry, rather than by their merits, risks demeaning their dignity.

Upholding affirmative action in 2003, in Grutter v. Bollinger, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor argued that it served the intellectual purpose of a university. Writing for the majority, she described how the University of Michigan aspired to enhance diversity not only to improve the prospects of certain groups of students, but also to enrich everyone’s education.

Ms. Fisher argues that diversity may be achieved in other ways, without considering race. Before resorting to the use of race or ethnicity in admissions, the University of Texas must offer “actual evidence, rather than overbroad generalizations about the value of favored or disfavored groups” to show that “the alleged interest was substantial enough to justify the use of race.”

Our research provides such evidence. Diversity improves the way people think. By disrupting conformity, racial and ethnic diversity prompts people to scrutinize facts, think more deeply and develop their own opinions. Our findings show that such diversity actually benefits everyone, minorities and majority alike.

To study the effects of ethnic and racial diversity, we conducted a series of experiments in which participants competed in groups to find accurate answers to problems. In a situation much like a classroom, we started by presenting each participant individually with information and a task: to calculate accurate prices for simulated stocks. First, we collected individual answers, and then (to see how committed participants were to their answers), we let them buy and sell those stocks to the others, using real money. Participants got to keep any profit they made.

When trading, participants could observe the behavior of their counterparts and decide what to make of it. Think of yourself in similar situations: Interacting with others can bring new ideas into view, but it can also cause you to adopt popular but wrong ones.

We assigned each participant to a group that was either homogeneous or diverse (meaning that it included at least one participant of another ethnicity or race). To ascertain that we were measuring the effects of diversity, not culture or history, we examined a variety of ethnic and racial groups. In Texas, we included the expected mix of whites, Latinos and African-Americans. In Singapore, we studied people who were Chinese, Indian and Malay. (The results were published with our co-authors, Evan P. Apfelbaum, Mark Bernard, Valerie L. Bartelt and Edward J. Zajac.)

The findings were striking. When participants were in diverse company, their answers were 58 percent more accurate. The prices they chose were much closer to the true values of the stocks. As they spent time interacting in diverse groups, their performance improved.

In homogeneous groups, whether in the United States or in Asia, the opposite happened. When surrounded by others of the same ethnicity or race, participants were more likely to copy others, in the wrong direction. Mistakes spread as participants seemingly put undue trust in others’ answers, mindlessly imitating them. In the diverse groups, across ethnicities and locales, participants were more likely to distinguish between wrong and accurate answers. Diversity brought cognitive friction that enhanced deliberation.

For our study, we intentionally chose a situation that required analytical thinking, seemingly unaffected by ethnicity or race. We wanted to understand whether the benefits of diversity stem, as the common thinking has it, from some special perspectives or skills of minorities.

What we actually found is that these benefits can arise merely from the very presence of minorities. In the initial responses, which were made before participants interacted, there were no statistically significant differences between participants in the homogeneous or diverse groups. Minority members did not bring some special knowledge.

The differences emerged only when participants began interacting with one another. When surrounded by people “like ourselves,” we are easily influenced, more likely to fall for wrong ideas. Diversity prompts better, critical thinking. It contributes to error detection. It keeps us from drifting toward miscalculation.

Our findings suggest that racial and ethnic diversity matter for learning, the core purpose of a university. Increasing diversity is not only a way to let the historically disadvantaged into college, but also to promote sharper thinking for everyone.

When it comes to diversity in the lecture halls themselves, universities can do much better. A commendable internal study by the University of Texas at Austin showed zero or just one African-American student in 90 percent of its typical undergraduate classrooms. Imagine how much students might be getting wrong, how much they are conforming to comfortable ideas and ultimately how much they could be underperforming because of this.

Ethnic diversity is like fresh air: It benefits everybody who experiences it. By disrupting conformity it produces a public good. To step back from the goal of diverse classrooms would deprive all students, regardless of their racial or ethnic background, of the opportunity to benefit from the improved cognitive performance that diversity promotes.

Repost from New York Times

The Death of Ivan Ilych, by Leo Tolstoy

"Hailed as one of the world's supreme masterpieces on the subject of death and dying, The Death of Ivan Ilyich is the story of a worldly careerist, a high court judge who has never given the inevitability of his death so much as a passing thought. But one day death announces itself to him, and to his shocked surprise he is brought face to face with his own mortality. How, Tolstoy asks, does an unreflective man confront his one and only moment of truth?

This short novel was the artistic culmination of a profound spiritual crisis in Tolstoy's life, a nine-year period following the publication of Anna Karenina during which he wrote not a word of fiction. A thoroughly absorbing and, at times, terrifying glimpse into the abyss of death, it is also a strong testament to the possibility of finding spiritual salvation."

You can buy it here

or download it here.

Stories Matter : John Green Style

"It is absolutely exhausting and infuriating and the more I let myself be stuck inside of [my body prison] the less I am able to acknowledge and celebrate the humanity of others or those who are distant from me who are fundamentally "other" the more the problems of people who live far away or live in circumstances that are different than mine feel like they are 'not my problems' . . .

Fiction for me, stories for me, are the only way out of that, out of this prison that I'm stuck inside of.

I can live inside the lives of someone else for a while. . ."

Stories Matter.

One Book Which Changed My Life Forever

Sorry, I couldn’t come up with “50 GREAT READS TO SUPERCHARGE YOUR PRODUCTIVITY.”

Instead, here is the first book which changed my life forever. There have been others, of course, but you never forget the first time.

The book which had the most change on my life was The Bridge to Terabithia.

Picture this — I am a young, nerdy 5th grader walking into a class full of rowdy kids. (Yes, even at age 11, I thought they were rowdy). They stampeded through the hallways. I sat and read.

Our teacher tasked us with a wonderful book about woods and magical creatures. I soaked in the world. I traveled with the two main characters (no, I don’t remember their names, and I’m not going to google them to sound smarter).

This book pulled me in. I can’t remember an earlier experience which so engaged my heart, soul, and mind.

I didn’t just read the book, I was IN the book.

Pure nirvana.

AND THEN.

I read ahead of the chapters for the day. This was not a new thing. I remember flipping over the pages happily, wondering what mischief would happen next.

Here’s what happened next:

The girl died.

SHE DIED.

She crushed her head on a stupid rock, and she died. A needless, pointless, useless tragedy. Later, the boy character ate pancakes or something.

I couldn’t understand — how could she have died? Kids my age don’t die, even in books. They are invincible. If she died, would I die? Would everyone in my classroom die?

I finished the book in a daze. I walked across the room, trying to get to the bathroom.

The teacher grabbed my arm before I could make it out the door.

“Todd, are you okay?”

I wrenched my eyes shut and nodded my head, trying to prevent the inevitable. Then, I dropped my head to my chin and released the raw emotion which had been clawing its way out of my ribs and up my throat for the last hour. There, in front of all my friends and classmates, I squalled like a baby.

A book made me feel this way.

On that day, I learned words have the ability to change the way you think. I learned stories are more powerful, sometimes, than actual experiences. I learned reading ahead is not always the best idea.

Most importantly, I learned art can make you feel. It can make you think. It can create an emotion — not the fleeting emotion of a thought, but one deep enough and strong enough to change a life forever. One so powerful you tell strangers on the Internet about it 16 years later.

Words matter. Stories matter.

And they always will.

— TB

Repost from Todd Brison

These Algerian women were forced to remove their veils to be photographed in 1960

THEIR PORTRAITS ARE PROBLEMATIC, BUT STUNNING

If looks could kill, then a camera aimed at an unwilling subject is an instrument of torture.

Marc Garanger knew this in Algeria, in 1960 when he was tasked by his commanding French army officer with snapping ID photos of their female prisoners. France was six years into supressing a guerrilla war for independence in the north African colony, and Muslim and Berber villagers were being arrested en masse for suspected ties to the insurgent National Liberation Front. As his regiment’s official photographer, Garanger made thousands of portraits of rural women against their will. Many of them were forced to remove their headscarves and veils for the photo, revealing themselves for the first time to the hostile gaze of strange men.

Their observer, Garanger was also their oppressor.

For more of this article and Rian Dundon's work, click here.

(Non)Traditional New Year's Post : Resolve

The World of Languages in Simple Infographics

THIS CIRCLE WAS CREATED by Alberto Lucas Lopez for the South China Morning Post. It’s an easy way to wrap your head around the 4.1 billion people around the world who speak (as their native tongue) one of 23 of the world’s most-spoken languages.

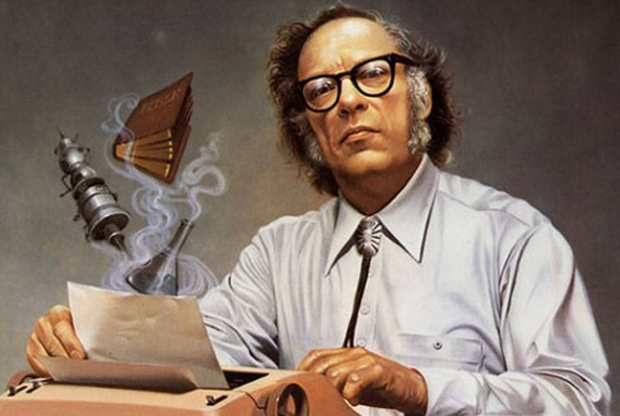

Isaac Asimov : How to Never Run Out of Ideas . . .

If there’s one word to describe Isaac Asimov, it’s “prolific”.

To match the number of novels, letters, essays and other scribblings Asimov produced in his lifetime, you would have to write a full-length novel every two weeks for 25 years.

Why was Asimov able to have so many good ideas when the rest of us seem to only have 1 or 2 in a lifetime? To find out, I looked into Asimov’s autobiography, It’s Been a Good Life.

Asimov wasn’t born writing 8 hours a day 7 days a week. He tore up pages, he got frustrated and he failed over and over and over again. In his autobiography, Asimov shares the tactics and strategies he developed to never run out of ideas again.

Let’s steal everything we can.

1. NEVER STOP LEARNING

Asimov wasn’t just a science fiction writer. He had a PhD in chemistry from Columbia. He wrote on physics. He wrote on ancient history. Hell, he even wrote a book on the Bible.

Why was he able to write so widely in an age of myopic specialization?

Unlike modern day “professionals”, Asimov’s learning didn’t end with a degree—

“I couldn’t possibly write the variety of books I manage to do out of the knowledge I had gained in school alone. I had to keep a program of self-education in process. My library of reference books grew and I found I had to sweat over them in my constant fear that I might misunderstand a point that to someone knowledgeable in the subject would be a ludicrously simple one.”

To have good ideas, we need to consume good ideas too. The diploma isn’t the end. If anything, it’s the beginning.

Growing up, Asimov read everything —

“All this incredibly miscellaneous reading, the result of lack of guidance, left its indelible mark. My interest was aroused in twenty different directions and all those interests remained. I have written books on mythology, on the Bible, on Shakespeare, on history, on science, and so on.”

Read widely. Follow your curiosity. Never stop investing in yourself.

2. DON’T FIGHT THE STUCK

It’s refreshing to know that, like myself, Asimov often got stuck —

Frequently, when I am at work on a science-fiction novel, I find myself heartily sick of it and unable to write another word.

Getting stuck is normal. It’s what happens next, our reaction, that separates the professional from the amateur.

Asimov didn’t let getting stuck stop him. Over the years, he developed a strategy…

I don’t stare at blank sheets of paper. I don’t spend days and nights cudgeling a head that is empty of ideas. Instead, I simply leave the novel and go on to any of the dozen other projects that are on tap. I write an editorial, or an essay, or a short story, or work on one of my nonfiction books. By the time I’ve grown tired of these things, my mind has been able to do its proper work and fill up again. I return to my novel and find myself able to write easily once more.

When writing this article, I got so frustrated that I dropped it and worked on other projects for 2 weeks. Now that I’ve created space, everything feels much, much easier.

The brain works in mysterious ways. By stepping aside, finding other projects and actively ignoring something, our subconscious creates space for ideas to grow.

3. BEWARE THE RESISTANCE

All creatives — be they entrepreneurs, writers or artists — know the fear of giving shape to ideas. Once we bring something into the world, it’s forever naked to rejection and criticism by millions of angry eyes.

Sometimes, after publishing an article, I am so afraid that I will actively avoid all comments and email correspondence…

This fear is the creative’s greatest enemy. In the The War of Art, Steven Pressfield gives the fear a name.

He calls it Resistance.

Asimov knows the Resistance too —

The ordinary writer is bound to be assailed by insecurities as he writes. Is the sentence he has just created a sensible one? Is it expressed as well as it might be? Would it sound better if it were written differently? The ordinary writer is therefore always revising, always chopping and changing, always trying on different ways of expressing himself, and, for all I know, never being entirely satisfied.

Self-doubt is the mind-killer.

I am a relentless editor. I’ve probably tweaked and re-tweaked this article a dozen times. It still looks like shit. But I must stop now, or I’ll never publish at all.

The fear of rejection makes us into “perfectionists”. But that perfectionism is just a shell. We draw into it when times are hard. It gives us safety… The safety of a lie.

The truth is, all of us have ideas. Little seeds of creativity waft in through the windowsills of the mind. The difference between Asimov and the rest of us is that we reject our ideas before giving them a chance.

After all, never having ideas means never having to fail.

4. LOWER YOUR STANDARDS

Asimov was fully against the pursuit of perfectionism. Trying to get everything right the first time, he says, is a big mistake.

Instead, get the basics down first —

Think of yourself as an artist making a sketch to get the composition clear in his mind, the blocks of color, the balance, and the rest. With that done, you can worry about the fine points.

Don’t try to paint the Mona Lisa on round one. Lower your standards. Make a test product, a temporary sketch or a rough draft.

At the same time, Asimov stresses self-assurance —

[A writer] can’t sit around doubting the quality of his writing. Rather, he has to love his own writing. I do.

Believe in your creations. This doesn’t mean you have to make the best in the world on every try. True confidence is about pushing boundaries, failing miserably, and having the strength to stand back up again.

We fail. We struggle. And that is why we succeed.

5. MAKE MORE STUFF

Interestingly, Asimov also recommends making MORE things as a cure for perfectionism —

By the time a particular book is published, the [writer] hasn’t much time to worry about how it will be received or how it will sell. By then he has already sold several others and is working on still others and it is these that concern him. This intensifies the peace and calm of his life.

If you have a new product coming out every few weeks, you simply don’t have time to dwell on failure.

This is why I try to write multiple articles a week instead of focusing on one “perfect” piece. It hurts less when something flops. Diversity is insurance of the mind.

6. THE SECRET SAUCE

A struggling writer friend of Asimov’s once asked him, “Where do you get your ideas?”

Asimov replied, “By thinking and thinking and thinking till I’m ready to kill myself. […] Did you ever think it was easy to get a good idea?”

Many of his nights were spent alone with his mind —

I couldn’t sleep last night so I lay awake thinking of an article to write and I’d think and think and cry at the sad parts. I had a wonderful night.

Nobody ever said having ideas was going to be easy.

If it were, it wouldn’t be worth doing.

REPOST FROM CHARLES CHU

(Non)Traditional Christmas Post 6/6 : A TRUE Christmas Story

(Non)Traditional Christmas Post 5/6 : From the Book of Babes

(Non)Traditional Christmas Post 4/6 : A History of Peace on Earth

Lunch Atop a Skyscraper

"As part of Time magazine’s recent selection of the 100 most influential photos of all time, art historian Christine Roussel talks about the story behind the iconic Lunch Atop a Skyscraper photograph of a group of construction workers on their lunch break. Interestingly, no one knows for sure who the workers were and who actually took the photograph."

A REPOST FROM KOTTKE.ORG

The Red Bow, by George Saunders

How to be brave: some stories about courage

Laura Olin runs the Everything Changes mailing list for The Awl and she asked her readers “about a time they’d been brave” (or perhaps when they’d wished they had been). Here are some of their answers.

I was raised in a pretty abusive household. When I was 14, I found a boarding school three thousand miles away, applied in secret, got a full scholarship, and left home. I haven’t lived at home since and have made it ten years later fully supporting myself in a city I love, a job I love, friends/community that I love. I sometimes think about that now, packing up everything and moving across the country without any support and building a new life for myself through a lot of luck and other people’s help, and know I probably couldn’t do it again. I left the worse place for paradise, both handed-out and self-made, and there’s nothing I’m prouder of.

Some regretted not having courage at times:

A few months ago, some coworkers made some antisemitic jokes in a team chat channel. I quit the channel and started looking for (and since found) a new job, but I didn’t say anything. I’ve thought about that time I didn’t say anything literally every day since. I wish I had been a better person.